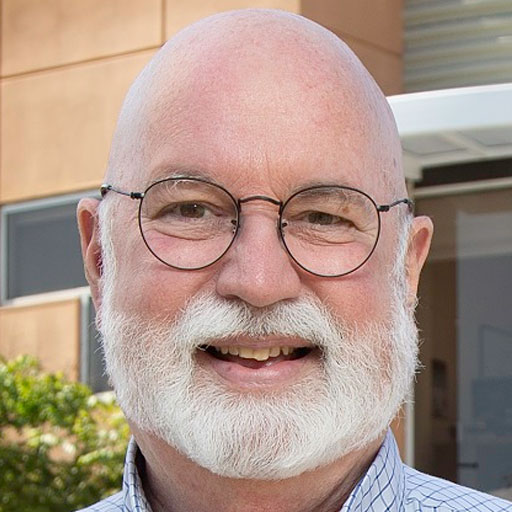

Gregory Boyle is the founder of Homeboy Industries in Los Angeles, the largest gang-intervention, rehabilitation, and re-entry program in the world.

In 1988 they started what would eventually become Homeboy Industries, which employs and trains former gang members in a range of social enterprises, as well as provides critical services to thousands of men and women who walk through its doors every year seeking a better life.

Father Boyle is the author of the 2010 New York Times-bestseller Tattoos on the Heart: The Power of Boundless Compassion. His second book, Barking to the Choir: The Power of Radical Kinship, was published in 2017. And his new and third book is now available, The Whole Language: The Power of Extravagant Tenderness.

He has received the California Peace Prize and been inducted into the California Hall of Fame. In 2014, President Obama named Father Boyle a Champion of Change. He received the University of Notre Dame’s 2017 Laetare Medal, the oldest honor given to American Catholics. In 2020, he served as a committee member of California Governor Gavin Newsom’s Economic and Job Recovery Task Force as a response to COVID-19 crisis. In the same year, Homeboy Industries was the recipient of the 2020 Hilton Humanitarian Prize validating 32 years of Fr. Greg’s vision and work by the organization for over three decades.

John Shegerian: This edition of the Impact podcast is brought to you by ERI. ERI has a mission to protect people, the planet, and your privacy and is the largest fully integrated IT and electronics asset disposition provider and cybersecurity-focused hardware destruction company in the United States, and maybe even the world. For more information on how ERI can help your business properly dispose of outdated electronic hardware devices, please visit eridirect.com.

John: Welcome to another edition of the Impact Podcast. I’m John Shegerian and I’m so honored to have a very, very long-time friend with me today, Father Greg Boyle. He’s the founder of Homeboy Industries. Father Greg, welcome to the Impact Podcast.

Father Greg Boyle: It’s great to be with you, John. Good to see you again.

John: Great to see you. Thirty years, when they, when it says in the Bible “blink of an eye”, man, they had it straight there. They had it really straight. So, it goes fast. Father Greg, you are known around the world for the Homeboy Industries and all the great work you’ve done with the kids in East L.A. and way beyond East L.A., and the speaking you’ve done around the world on this topic of love, of kinship, of transformational opportunities for our youth. But before we go there and also, today we’re going to be talking about your new book, which makes a great Christmas gift— the whole language, the power of extravagant tenderness. Tell us a little bit about your background Father Greg, where you grew up, how you got your calling to the Dolores Mission in Boyle Heights, and how we even got here?

Father Greg: Well, I’m from Los Angeles and my parents were from Los Angeles and their parents were from Los Angeles. So, a lot of generations here and family of eight. I was educated by the Jesuits so that kind of I was intrigued by them. They were prophetic. This was during the Vietnam war, I admired that and they would drag us to protest against the war, and then they were hilarious. So, for me, it was a combo burger of hilarity and prophetic that I liked. So I joined the Jesuits like the Pope is a Jesuit. So then, I studied and educated myself here and there and everywhere. And then I was assigned to the poorest parish in the city of Los Angeles, Dolores Mission. I spoke Spanish so… And it had the largest grouping of public housing West the Mississippi. It had the highest concentration of gang activity anywhere. We had 8 gangs in my parish that were at war with each other. And so, that’s how I… But I didn’t set out to do anything. I didn’t feel particularly called, I mean, I didn’t even know what a gang member was until I started burying kids in 1988.

We started the school and we started the jobs program mainly trying to find felony-friendly employers, and you were one of those felony-friendly employers. I remember trying to get a homies who were to be janitorial there at Grand Central Market many years ago. And then when we started all these crews and 1988, maintenance crew, landscaping crew, all made up of rival enemy gang members. And then the bakery came in ’92, and then homeboy tortillas right after that. So, anyway, I didn’t set out. We have special people come here to the headquarters, which is our 4th location, and it’s huge. Fifteen thousand folks a year walk through our doors, and now we have 10 social enterprises. But people will say, “Wow. How did you think this up?” and the truth is nobody thinks anything up. You evolve, you…

John: True. I’ll give you some of my memory. Of course, you and I both were in L.A. and we lived through what was then called of course “revisionist history”. It has a way of changing what things are called or what things mean, but when we were living there it was called the Rodney King Riots when we lived through the horrific period of early Spring of 1992. And that was a very weird period. I remembered now, my partner was my boss. I was just the number 2 guy at the Grand Central Market and we lost the guy. No one wanted to be in downtown because that’s where the riot started. We had the Bradbury Building as you know, we have the Grand Central Market, and that we lost the guy, the husband, and wife, who owned that practically brand-new tortilla. I harken back on you. I had watched you and I don’t remember when. It could have been 3 months prior to the riots. It could have been 6 months. My memory is a little foggy there, but I had watched you interviewed back then on 60 Minutes.

Father Greg: That’s right.

John: Back then, as you and I know, because we’re old enough to know this 60 Minutes was the place. There was no Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, Twitter, it was the place. There was no social media. So, people got their news and were moved by trends and things that were being highlighted on 60 Minutes. And you were one of those, really, you were in rare air. I remembered watching you be interviewed like, “Let me call this gentleman and see if he wants to bring his program,” which you had already started like you said in East L.A. in ’88 and bring it over to the tortilla. You were kind enough, on my cold call, to come over. We had coffee at Pascual Coffee, which was right across the aisle from the empty tortilla. You had the unbelievable courage and openness to say yes to this concept and yes to this idea. As you know much better than I do, the most repeated phrase in the Bible is “Be not afraid.” I always was so impressed by you because you started introducing me to your board in East L.A., the Proctor Pastoral Board and you introduced me to Mary and Peter, and Michael and all these wonderful human beings. What I sense with you was this courage and fearlessness. Where did you get that from? What informed you? It’s one thing to become a Jesuit priest. It’s another thing to be assigned to the poorest parish in East L.A. But you had this openness and courage and fearlessness that I think has carried you your whole lifetime because the success you’ve made and the impact you’ve made on hundreds of thousands of young people, and also people like me— and we’ll get to that in a little while— has been immeasurable. So, where did that come from? Where was that in your DNA?

Father Greg: Well, I don’t, you know, I thank you for that. I mean, I don’t always particularly feels fearless, but I am kind of a mantra, you know, where I just pray be fearless for me, and then you kind of feel sustained whenever you feel distressed and give us this day our daily bread. Everybody has distress. So you just hope to be more and more, a sturdier soul in the world where you can withstand things. But for me, it’s never, any of this work has never been a grim duty. It’s always been delighting in people. I mean this morning I, just in my office, just belly laughs, and people are so smart and people are so tender and people are so thoroughly unshakably good. So it’s a joy to kind of be with people as they discover the truth of who they are. And together, we all love each other into wholeness. We all walk each other home and that’s kind of the goal. So but yeah, you’re right. The thing about in scripture, 365 times one for every day is one form or another of “be not afraid.”

John: Honestly, and we’re going to… I think about you. And when you think about the people in your life that made the biggest impact, you’re the one who’s made the biggest impact, and I’m going to talk that more later on my life. Actually, you and I are going to have a chance to be together in the near future. And I’m going to be introducing you and I’m going to talk about it more when I do that as well. But you wrote “tattoos on the heart”, which was a wonderful book, I read. And then you wrote “barking to the choir”, and now you’ve written, and I’ve just read over the last weekend this wonderful book, “A whole language, the power of extravagant tenderness”. Tell me about this latest book and why it’s important for you to get down your experiences and your feelings and where you think we’re at in this journey into books? And why this book is so important being it’s your latest?

Father Greg: Well, I don’t know. It’s a little bit like this headquarters here where I’m sitting, how do you think it up? Well, I don’t know.

[Laughter]

Father Greg: It sort of involved. The same thing with the book. The first book was, I had a storehouse of 20 years of stories and I thought… And people said you should write them down. And so I did. I never thought I’d write another book and then Simon & Schuster asked me to write another book and so I went. So the first book was in me. The second book was asked of me and the third book was kind of a combo burger of both, in me and asked of me. So and it’s a Trilogy and as much as it’s my power books, the power of boundless compassion, the power of radical kinship, and then the power of extravagant tenderness. So they’re all kind of have the same structure, they’re essays. They’re me thinking about subjects like death or the church or Pope, or God or whatever it was.

They’re just a vehicle to… Somebody called me a writer the other day. And I certainly don’t feel like one. I’ve written three books, but I don’t identify as a writer. I’m kind of more of a… I tell stories and I preached. So I’m at all our detention facilities in LA county. they’re numerous, and then prisons beyond that. I always preach and I always tell 3 stories in my homily. So these things are all collections of that kind of stuff.

John: You know for our listeners and viewers out there, first of all, I highly recommend this book as a wonderful Christmas gift. This is our Christmas special for the impact podcast. So I highly recommend this book and we’re going to also have some special signed copies from Father Greg to give away to some of our listeners who write into us.

You just talked about radical kinship. I want to read you a quote. Something that’s a paraphrase of something you’ve said it historically. But I want you to break it down for our listeners because I think it sums up a lot of who you are, and what drives you. If you go to the margin to make a difference, it’s about you. If you go to the margin for them to make you different, it’s about us, the word for that is kinship. Can you break that down for our listeners and viewers who haven’t had the pleasure, the joy of meeting you and seeing you do your great work, Father Greg?

Father Greg: Yeah, you know, you go to the margins because that’s the only way they’re going to get erased. So you don’t go there to fix, or rescue, or save people, or even transform lives. Here at homeboy lives get transformed, but I don’t do it. I don’t transform people. We don’t do that for each other, but it happens in a kind of a culture in a context of tenderness and that’s our methodology. So that’s the hope.

People talk about burnout. If you go to the margins to make a difference you’re going to burn out because you’ve allowed it to become about you. But if you go to the margins to be made different, to have your heart altered, to be reached by people, then it’s about us, and it’s eternally replenishing. You’re never going to burn out. So that’s just never going to happen.

I learned that lesson early on probably 10 years in. I’ve never been close to burnout since then and I think it’s because you just can’t ever allow it to become about you. Then it’s not about success or failure. You know what Mother Teresa says, “we’re not called to be successful. We’re called to be faithful.” So you just try to stay faithful to a methodology, a way of proceeding in the world. And then success is, I don’t know, God’s business, but it’s not my business. And so it’s not about evidence-based outcomes.

I just had a group of students here doing an interview and they were saying, talk about your failures. I go, “I don’t know what you’re talking about.” I mean, I don’t believe in failure, but I also don’t believe in success. I just believe in you find the methodology, the way you want to proceed and you try to stay faithful to that. But if there are successes, then there are failures. If there are good people, then there are bad people and I don’t believe in any of that. I believe we’re all unshakably good and we all belong to each other. Now, roll up your sleeves and do the best you can.

John: It served you. Well, that way of operating has obviously served you really well. For our listeners and viewers of just turned in, we’re so honored to have with us, Father Greg Boyle. He’s the founder of Homeboy Industries. To find Father Greg, all of his colleagues, and learn much more about the great work he’s doing not only in East LA but around the United States, with all these outposts and around the world in terms of his speaking and sharing his stories, please go to www.homeboyindustries.org. Or you could also find his new book on the “Whole language, the power of extravagant tenderness”, amazon.com, Barnes and Noble, and other great bookstores in your local community or online.

Father Greg, we just all live through another black mark episode on American history, of course, you and I were in L.A. at the same time when the Rodney King riots happened. And then last year we live through the summer of last year, the spring of last year, the tragedies in Minneapolis and way beyond across America. And in one way, I was watching television and thinking to myself and watching the news that man in 30 years, we haven’t even come that far. The systemic racism in America, things haven’t improved. I’d love to hear you’re take given that you’re a great leader and great leaders know how to define reality and then give hope. I’d love you to share your vision on what happened on your take, first of all, what happened last year and how far we really come since the riots that put us together in ’92 and where we going from here as a country and as a people?

Father Greg: Yeah, I mean, I think we have made progress. I mean Barack Obama used to say, “if you don’t think we’ve made progress then you’re not paying attention.” And it’s true. I look at gang violence in Los Angeles County. When I met you, we had 1,000 gang-related homicides in Los Angeles. So, what’s happened to that number since? Well, that’s been cut in half and cut in half again. And chiefs of police would certainly include homeboy as a having had a singular impact on public safety and in Los Angeles. And that’s because right about the time I met you, we started to, there was no such thing as an exit ramp. So you could just say no to gang violence, but there was no way for gang members to get off that crazy freeway.

John: Absolutely. [crosstalk]

Father Greg: Yeah. And then you had it.

John: Yeah, you became the facilitator for that, your organization.

Father Greg: But then it was like even symbolic. So even if folks didn’t walk through our doors, they knew that such a place existed and they knew that there was hope.

John: Right.

Father Greg: And so that was kind of key so that change things. I also think people are starting to see things differently. And I hope that we get just as we’ve had a kind of a more sophisticated take on crime in general. The largest gang and the largest mental hospital on the planet Earth is LA County jail, which should tell us something about how wrongheaded our approach has been. But we think it’s about bad people doing bad things, but it’s really about despair. And it’s about traumatized people and it’s about mentally ill people. So if we infused hope for folks for whom hope is foreign, or if we helped heal damaged people, or if we deliver mental health services in a culturally appropriate way, we make even more progress. But nobody’s ever found a treatment plan that was any damn good, that was born from a bad diagnosis. You and I remember the days when the diagnosis was bad.

John: Right.

Father Greg: And now we’ve really changed the diagnosis which is hopeful. And racism is, I think how our mental health crisis presents itself. People can act out in a way that’s really quite alarming, but nobody healthy engage it. Nobody healthy engages in violence. These aren’t rational acts but coming from healthy actors. Even yesterday, it feels unrelated. But you have a fifteen-year-old kid who kills people at a school in Michigan. And police are going [inaudible], we can’t find the motive. I go, “well, imagine a motive that would make sense to that action.” He got a D on his math test. There is no motive. Nobody healthy does such a thing, right? So rather than demonize him, how do we help people and help ourselves even in terms of sensible gun laws? How do we help each other? This is an indicator. It’s a symptom that were not well and none of us are well until all of us are well.

I think it’s important to… The homies here always talk about find the thorn underneath. So you want to find the thing that undergirds all, vexing social dilemma that kind of has us all scratching our heads. And we belong to each other and everybody’s unshakably good. Begin there, and I think we’ll make progress.

John: I grew up in Queens, New York. I grew up in integrated schools in New York City. And when I first met you, you broke things down, so simply for me. And you made it clear to me what mission we were on. Of course, we were doing the tortilla together. So you said to me, John these young kids that are either gang impacted or already have been involved with gangs and are trying to get out. You said, “if they don’t get out of that gang life, they’re going to end up in one of two places.” You made it real clear to me, jail or dead. And those are obviously horrific options. Excuse me. And then you laid on me you’re unbelievable tagline which is still probably rings more truth today than it even did the day I met you in ’92, that nothing stops a bullet faster than a job.

And it’s that simple in many ways. I know, there’s like you said so many other layers to societal, systemic, legacy, mental, and other mental health issues, and other things that layer into this. But just the simplicity of a job is such a genius way of approaching this and getting people to want to lean in and participate and support your great organization. How is that tagline that you created now over 3 decades ago, more true than ever before?

Father Greg: Well it’s interesting though. When we listen to gang members, they’d say, if only we had a job and so nothing stops a bullet like a job was born.

John: Right.

Father Greg: That’s one by listening to gang member. I think once we knew gang member, then we went, “Oh, this is about healing.” An employed gang member may or may not go back to prison or educated one may or may not. But then we… Fifteen years ago, we came to the conclusion that a healed gang member will not ever re-offend. Will not. And once we knew that we thought “well, what if as a society we no longer punished wound, but we sought to heal it.” Then we set about to do that. So that kind of changed a lot of what we did. We have therapy and groups and it’s the whole culture of the place and tattoo removal and all these other services that help people inhabit the truth of who they are.

So our program now is 18 months and it’s parallels the time it takes for infant to attach to a caregiver. So it’s what were engaged in really is attachment repair. So how do you repair what has been severed? So that people can be sturdier. They can be resilient and then they leave us after 18 months. And now the world’s going to throw at them what it will, but this time they’re not going to be toppled by it.

John: Right.

Father Greg: But if they were just employed, that’s what we were trying to find. We’d started to discover that. Now, you know that guy, we didn’t find him a job. We found him a career, but then his lady left him and it send him in this spiral and now he’s doing 125 years to life at Folsom. So that happened and it made us kind of question what the emphasis is. So now it’s kind of human-centered. The traumatized are more likely to cause trauma then we discovered that the cherished person will be able to find their way to the joy there is in cherishing themselves and others.

It kind of shifted probably 15 years ago in midstream, which was good. We were learning. Even in the early days, just before I met you, I did a lot of shuttle diplomacy, with the 8 gangs that were at war. [crosstalk]

John: Right. I remember.

Father Greg: Yes, ceasefires and truces and peace treaties. And I always say I don’t regret that I did it but I’d never do it again because then you learn. You learn that this the kind of… If you work with gangs it’ll just serve the cohesion of gangs. And it supplies oxygen to gangs, and you don’t want to do that. So we’re kind of like a rehab center. It takes what it takes, and in recover, you have to walk through the door. We don’t coax you or we don’t even invite you. If everybody knows with 120,000 gang members in LA county, every single one knows who we are and what we do.

John: That’s true. [crosstalk] [inaudible]

Father Greg: But they have to walk through the doors otherwise it doesn’t work.

John: Father Greg talked a little bit about how big you and your colleagues have made Homeboys since ’92. Since where is it grown? How big is it now? And I’ve been to the headquarters, I’ve been to the bakery and had lunch with Tom down there a couple times and but how many young people are you working with on a regular basis that are matriculating through your amazing program? And then how many seeds have you set? And I want to go back to that in a little while, after you answer this question, how many seeds have you set for other outposts around, the nation around the world?

Father Greg: Yeah, maybe I’ll begin with that part. When we first moved here, we’d get delegations. Like I remember, the [inaudible] came in, the stakeholders, mayor, chief of police and they wanted us to airlift homeboy into Wichita. This would have been 2008 and we had to decide, do we want to become the McDonald’s of gang intervention programs? But we decided not to do that, so we said, “Hey, we’ll give you technical assistance. So start your own thing. You can be a partner with us, just don’t call it Homeboy Industries because I have a hard time enough, raising money for us. I don’t want to have to worry about [inaudible].” So they started, I remember it was called the Central Cafe, and so was modeled on Homeboy and it was a gang members, and they start to add things after they started the restaurant. Things like therapy and classes and that kind of thing. And so now we have what we call the global Homeboy Network. So they’re 350 programs modeled on Homeboy, 300 in the country 50 outside, and they all have names like Braveheart Industries in Glasgow Scotland.

John: Wow.

Father Greg: Or Rise Up Industries in San Diego. They always begin with some kind of business, rise up has kind of manufacture stuff. But they all kind of have embraced the methodology of Homeboy. So we gather every August for 3 days and people gather. We did it virtually last year and the year before. And we just kind of share best practices and people report on their progress. And so it’s a way of proceeding that we’re finding too. It’s not just obviously gang because not everybody has gang stuff.

John: Right.

Father Greg: Sydney, Australia notes for disaffected youth and in Detroit, it’s for homeless and in some other places addressing the mental health issue. So people look at intractable social dilemma, and then they say “well, this is a methodology that may well help us.”

John: Understood.

Father Greg: So we have at any given time, 500 trainees, probably and then another hundred core and another hundred senior staff.

John: Wow, and with regards to fundraising, you mentioned that, you know, it’s hard enough to raise money to do the great work you’ve done. You’ve almost had to constantly also be fundraising at the same time besides managing all this enterprise that you’ve created, different businesses, and then the health care, and mental health care services that you offer. How was the fundraising gone? Talk a little bit about that journey, not just today, because I know some great things happen over the last year, which I want you to talk about, but I know it wasn’t always easy no matter how much great publicity came your way for the important work, you’re doing a lot of people were excited about what you’re doing, but wouldn’t write the checks. Explain climbing that mountain.

Father Greg: Well, the first 10 years, from ’88 to ’98 is what we would call the decade of death. And so when we began, the gang members obviously for those 10 years were highly demonized by everybody but especially law enforcement. So if the gang member was the enemy, then it was a short hop to demonize this priest for helping the enemy. So the friend of our enemy is our enemy. [crosstalk] [Inaudible] That was clear for 10 years. We got hate mail, death threats, bomb threats. Never from gang members because it was always clear to them. But you know. And then that changed, so we went from tough-on-crime to smart on crime and that the opposite of tough was not soft, but smart. And so that changed. It really did change and it had an impact on the numbers. Once we got through that decade of death. But it was hard like you said, people didn’t write checks. So we had a moment there in 2010 where I had to lay off 300 people and we just couldn’t, it was just really hard. So we had to make hard decisions. And now, we’re 40-million-dollar annual operation. And we have 10 social enterprises, mainly restaurants, bakeries, silk screening, which has been around for 27 years. And then Homeboy electronic recycling, which you know very well and have been very helpful with guidance. And so all of them employee of gang members and every person who works here has to work with multiple enemies. People they used to shoot at so it’s not only just a paycheck. It’s gets to put a human face on their enemies.

John: Father Greg, I know we have a time. We have a time…

Father Greg: I have to go meet with the Secretary of Labor. So he awaits me.

John: And I am not that important. So I’m going to let you go in a minute.

Father Greg: No, I’d rather be with you. Thank you very much.

John: You haven’t changed at all but I do want to say.

Father Greg: [Inaudible] see you in a bit.

John: Yeah, we’re going to see each other. But I do want to say this, I think as part of the story that gets lost a little. And this is really important that I want to share with you because this is a very personal part. When you and I got together, there was no such thing. It wasn’t taught in any University and the two words, social entrepreneurship never were used together. And you just by who you were and the impact you made on my life and my wife’s life and what you taught us going into Homeboy tortillas. And then post that experience, we decided as a husband and wife that we never wanted to do a another business that just made a profit. It had to have a purpose, a greater purpose, and a greater mission.

And one thing that I’ve enjoyed so much over the years is tracking some of the people that are like me that were affected by you. So, for instance, what I mean by that is, Jackie Robinson said “a life is meaningless except for its impact on other lives.” And you have not only had a massive impact on all these homeboy and homegirl lives, but just think about all the Kabir Stokes, and Andrea [inaudible], and John [inaudible] and Tammy [inaudible] that you literally molded and impacted to want to become social entrepreneurs. Before they resent before it was ever a thing, and never ever even a title, but people who just wanted to make the community better they lived in but make a profit along the way as part of the process. And I wonder how many John [inaudible], Kabir Stokes, Andrea [inaudible] that would come forward that said it’s because of Father Greg Boyle. There’s I’m sure a Cadre, hundreds if not, thousands of us that you’ve created. Now just think about my recycling company, before I had a recycling company, I democratize student lending online with a company called financial aid.com. That was because of you. And then I invested in a company called Engage because it was led by a young tech guy who was blind. When’s the last time you turned on Bloomberg or CNBC or the New York Times and saw a tech guy running a big company who was actually handicapped? And there’s 61 million handicapped, marginalized people in this country.

So like you said, it’s not just about gangs. It’s going to the margins and addiction centers, homeless, handicapped and so many other areas that we’ve taken the light that you’ve shared with us and then been able to exercise it in so many other ways including with gang impacted youth as well. But like you said, the margins exist in so many areas of society. And there’s so many of us that are graduates of the Greg Boyle School of social entrepreneurship mission-based work, that it would be fun one day to get us all together because I know Kabira personally, she’s a good friend. I know, Andrea personally, and I know there’s lots of others of us out there that adhere to the Greg Boyle School of wisdom and thought and I just want to say thank you for that because, without you, none of what I’ve done would have existed. So that’s why I was really excited to have you on today.

Father Greg: Likewise John. It’s an honor to know you and I look forward to seeing you in a matter of a day or so.

John: For our listeners and viewers out there to get involved, to donate your time, money, or otherwise go to www.homeboyindustries.org. Father Greg, all his colleagues are there. You can donate your time, your money, and other things. There’s a lot of ways to get involved, please buy for the holidays or post-holidays, the whole language the power of extravagant tenderness. It’s on amazon.com, Barnes and Noble, and other great bookstores. Father Greg, God bless you. Thank you for what you’ve done for my family. Thank you for what you’ve done for Los Angeles and everyone you’ve touched over the last 35 or so years. You’re a blessing. I wish we had thousands more of you, but unfortunately, we don’t. And I wish you continued great work, and I can’t wait to give you a hug in person. I get to introduce you in the near future.

Father Greg: It’s good. Thank you very much, John. Stay well.

John: Take care. Bye-bye.

John: This edition of the impact podcast is brought to you by ERI. ERI has a mission to protect people, the planet, and your privacy and is the largest fully integrated IT and electronics asset disposition provider and cybersecurity-focused hardware destruction company in the United States and maybe even the world. For more information on how ERI can help your business properly dispose of outdated electronic hardware devices, please visit eridirect.com.