-

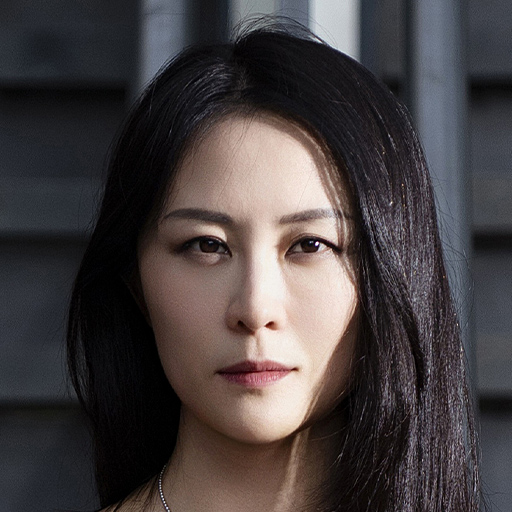

Keyu Jin

Global Economist

John Shegerian: Do you have a suggestion for a Rockstar Impact Podcast guest? Go to impactpodcast.com and just click “Be a Guest” to recommend someone today.

Dr. Keyu Jin is a global economist who was a tenured professor at the London school of economics for 15 years, and is currently affiliated with HKUST and Harvard University. She is the author of critically-acclaimed “The New China Playbook.” She is from Beijing, China, and holds a B.A., M.A. and Phd from Harvard University.

John: This edition of the Impact Podcast is brought to you by ERI. ERI has a mission to protect people, the planet, and your privacy, and is the largest fully integrated IT and electronics asset disposition provider and cybersecurity-focused hardware destruction company in the United States, and maybe even the world. For more information on how ERI can help your business properly dispose of outdated electronic hardware devices, please visit eridirect.com. This episode of the Impact Podcast is brought to you by Closed Loop Partners. Closed Loop Partners is a leading circular economy investor in the United States, with an extensive network of Fortune 500 corporate investors, family offices, institutional investors, industry experts, and impact partners. Closed Loop’s platform spans the arc of capital from venture capital to private equity, bridging gaps and fostering synergies to scale the circular economy. To find Closed Loop Partners, please go to www.closedlooppartners.com

John: Welcome to another edition of the Impact Podcast. I’m John Shegerian, and this is a very special edition. We’re so honored to have with us today Dr. Keyu Jin. She’s a global economist, professor of economics, and the author of this wonderful book, ‘The New China Playbook’. Welcome, Keyu, to the Impact Podcast.

Dr. Keyu: Thank you so much, John. It’s great to be with you.

John: Keyu, before we get talking about all the important work you do as an economist, as a professor, and as, of course, a well-known author, I’d love to talk a little bit about your background. You grew up in Beijing, and you’ve written about growing up with the planned blackouts in Beijing and reading by candlelight with your father. Then you moved to New York City as a 14-year-old. Do I have this right?

Dr. Keyu: Yeah, that was my story.

John: And [inaudible] all alone.

Dr. Keyu: Yeah, we considered it a tremendous opportunity. In fact, I thought I was going to a great school. Then my parents said, “Oh, it’s in the Bronx. Okay, we’re going to send our teenage daughter all alone, no boarding school, to the Bronx.” And then it ended up being one of the best schools in the U.S.. Thankfully, we had no idea about the school, though.

John: So, Keyu, wait a second. A couple of things that I’ve read about you, that was supposed to be for one week, if I’m not mistaken, and it became 3 years or so?

Dr. Keyu: Well, the American first family thought they were hosting me for a week, like a real exchange student visiting. And then I said, “Oh, no, I’m staying for three years.” Luckily, they liked me, and they wanted to keep me, but we had to try at least for a week.

John: The school you went to, I believe, I went to McBurney, which didn’t exist when you went to school, but my rival when I was growing up was Horace Mann.

Dr. Keyu: Yep, that was where I went to. I was supposed to go to Sidwell Friends because there was this great sinologist historian, Dr. Weiss, who wanted to have a Chinese student back in the 1990s, and he chose me. He then became headmaster of Horace Mann High School, so he took me with him. Therefore, I thought I was going to DC, and then I ended up in New York, and we had to find a host family. It was all very coincidental, but anyway, it worked out.

John: Now, your dad was quite a well-known person in China himself.

Dr. Keyu: [inaudible] he was assistant minister of finance, not quite as well known as he is now, perhaps. I think the more relevant part of it is that he was a true English literature scholar, a Shakespearean scholar to be exact. He’d written books on Victorian poetry and Shakespearean grammar. So I always had this idea, this fantasy, that I would go study in the U.S. with them or without them. That’s when I decided to leave at the first opportunity, at the age of 14.

John: And they were extraordinarily happy about this and excited about the experience and exposure you’d get there? Or was this more of your doing, and you had to convince them to do this?

Dr. Keyu: I think my parents, like many Chinese parents, are willing to make sacrifices for their children. I think they were very worried. Remember, back in the 1990s, we did not have Skype. We did not even really use the internet all that much. Remember the AOL dial, dial, dial?

John: ’97 was a year before Google started. It was a year before Google was founded.

Dr. Keyu: It took a while before Google really became very prominent. So it was hard to communicate. Telephone calls were extremely expensive, and I wasn’t able to visit them very often. So I think they made a sacrifice. Most importantly, to let their only child, and this is a big theme, of course, in my book, The One Child Policy, to let their only daughter go to the U.S., when you’d heard of so many horror stories of high school students in the U.S., I think, was a big sacrifice. But they understood it was good for my future, and they knew that I wanted to go, so they let me.

John: What was your experience like at Horace Mann?

Dr. Keyu: It was a bit of a shock, to be very frank. Of course, it was an extraordinary experience. I had never dreamt of being in a school, comparing back to China, where we were lighting up, marching around a campus at a fixed hour every morning, in school uniforms, very disciplined, 60 students per class, and everyone studying really hard. We had really nothing else to write in American school, where the first time I went into a class, it happened to be history class. The opening line of my history teacher was, “Question authority. Question the textbook,” and I’m like, “What? First of all, to raise questions was already very foreign to me, but to question the textbook, to question authority, and to open your mind, to have a free, open mind; I didn’t really understand what that meant. So that, and also, students were treated like adults. I think high school in the U.S. represents something deeper about American society, which I later came to grasp. It was really shocking already at that time that there were cliques, and everybody sat with the same group of people during lunch, which was just so wild for me. You had to belong to a group; that’s how the identity was formed. I think a lot of it explains a lot of our current president’s behavior. I think it explained a lot of the mentality between the U.S. dealing with China, and so forth, but that was not at all what a Chinese high school student was like. Of course, we had a very homogeneous, uniform environment. People had really only one objective, which was to do well academically in school. So it was a very interesting, although not without surprises, that kind of experience, but academically, it was also great.

John: Were the students accepting, welcoming, and warm to you when you arrived?

Dr. Keyu: I think they were open-minded to having a Chinese student coming from the mainland, because back in the 1990s, even late 1990s, there were very few. There were no international students at Horace Mann, to be very frank. Now, there’s many Chinese students studying in high school, but back then it was very rare. Yeah, they accepted me, I think it was that it took time, but the whole social atmosphere is very interesting. It’s also very strange, to some degree, that in high school, it was a microcosm of society. That was something I was not used to. I didn’t really quite find my group, let’s put it that way, but over time, I have built some very good individual friendships.

John: That’s so great. The host family that hosted you, do you still know them? Do you still stay in touch with them?

Dr. Keyu: Yeah, we’re in touch. It was very funny because Oliver Koppell was running for state attorney general against Eliot Spitzer. I think a well-known name back then, in the 90s. Mr. Koppell was briefly state attorney general of New York, and it was a very avid political family. So you can imagine the [inaudible] debates we had, when I’m explaining to them what China was really like versus what they were reading in the New York Times. And also explaining to people in the Democratic Party, when we went to these conventions, what China was really like, rather than what they had been reading about. It was really quite shocking to me that very sophisticated Americans had this very different picture of China from what I had known. They spoke about just Taiwan, Tibet, and human rights. That was the only thing they talked about. I remember that we were bidding for the Olympics of 2000. Eventually, China lost to Australia, but the streets were clean. Everyone was super psyched. There was so much exuberance with everything that was happening: the markets, the economy, the opportunities, everybody really embracing a very bright future. But all that was depicted in the West was kind of this very bleak, white oppression in the country that was not at all like that, in my view.

John: It’s so funny you say that, because I shared with you prior to us recording this that I’m 63 now. Growing up in New York City myself, always the impression in and around other colleagues, students, and friends of mine was that it was always depicted as China was sort of this big boogeyman to America. Unfortunately, less than 50% of Americans have passports. And when you really look at the numbers, less than 10% of them have ever been to Asia, nonetheless China. So much of misconceptions and misunderstandings happen because no one’s ever been and gotten a chance to really immerse themselves and see the wonderful culture and society that China has to offer. So the lack of knowledge and misunderstanding comes from just lack of wanting to go there and make yourself feel part of a local, live like a local when you go there. I started doing that in ’93. It’s been one of the greatest joys of my life. I’ve taken my son and my nephew, and it’s been transformative for them, but for those who haven’t been, it’s really hard to get their arms around it.

Dr. Keyu: The vast majority of people I talk to, if not everyone, who have been to China, Americans who have been to China, have generally a very positive view about China. Not 100%, because obviously, there are always things, but they like China. They see the real China. Look, America is a great country, but there is a big, big world out there, and given how the U.S. is so involved in the world, and facing now an extremely important big country, I think it’s absolutely critical to understand much more about this very different country. In some ways very different, in some ways very similar with the U.S., I’d argue. But the exchanges of students, like when I was going to school, were enormously helpful. It’s interesting we’re discussing this right now, especially about my personal experience, because the U.S. back then was so open to students like me, like us. They wanted us to be in the U.S.. They gave us enormous opportunities because they thought they were going to shape, or they were going to at least influence, future leaders around the world, and in many ways, they really have. The many international students that came to the U.S. and went back, regardless of where they stand on certain issues, don’t have to be completely westernized or completely Americanized, but there are certain qualities like openness, a free and open society that we all crave, the exchange of ideas, the exchange of knowledge, the importance of not making quick judgments. All that is taught to us by great American universities and it does change the world, but now it’s exactly the opposite. My niece is studying biology at UPenn, got a place as a PhD, has been getting an incredibly hard time getting a visa. It was exactly the opposite attitude when I was going to school.

John: To me, it just makes zero sense. It’s just hard for me to wrap my head around that, closing our open arms and now crossing them, and not being the warm country that we used to be with regard to exchange students and foreigners who have so much to bring and so much to share with our own society here. We’re an immigration nation. That’s what makes us great. My grandparents immigrated here; you came here, got educated here. We all owe so much to this country, and for us to turn our back on so many great young people just makes zero sense to me, where we are.

Dr. Keyu: And especially [inaudible] Africa’s[?] allies are the world’s youth, if you think about it. They are different. They’re very connected. They’re very multicultural, and they are the future. At least shape and try to influence the youth, and in many ways, they have, especially [inaudible] come and study in the U.S.. There are so many qualities that’s taught to you in American education that are so vital, and they do get brought back and transmitted back to their own home countries.

John: So obviously, you excelled at Horace Mann, and then you went on to Harvard, got an MA, and your PhD there. How was that experience over at Harvard after Horace Mann?

Dr. Keyu: Harvard was really a dream, to be honest, because it really was opening up my life to this vast richness of not only knowledge but also the international American student body, the life there, the learning there. Harvard is a very special place. Cambridge, Massachusetts, is a very special place. Many of us have said that we only realized that once we left. I was there for a very long time because I did my undergrad all the way to my PhD. So by the time I graduated, a third of my life alone was spent at Harvard. I hadn’t realized how special a place it really is. Thank goodness we still have that in America, the science, the innovation, the knowledge exchange, the really high standards. It is really the pinnacle of elite institutions and the fount of knowledge around the world, where I said, at least we have that. Well, it’s not so obvious these days, but again, that is really the emblem of American power for the rest of the world. That is something that is desired and aspired for so many Chinese students and students around the world.

John: You went on to teach for about 15 years as a tenured professor at the London School of Economics. So if I was to ask you, when you lie down at night and you think of yourself and your heart and soul, you have such a fascinating background of 15 years in London, of course, growing up in Beijing, and you’re Chinese born and bred, and then you got so much of your education in the West. Do you feel like you’re a total amalgam of the best of the West and the East?

Dr. Keyu: I really do like London, I have to say. Let’s say it’s in between. It’s somewhere in between the U.S. and China, both of which have their enormous qualities and extreme qualities and extreme challenges as well. London is kind of in between and is globally positioned. Of course, China’s home; you feel home here, but I think my life is still about the global connectivity. A lot of my work has to do with trying to communicate with people outside of China about China’s reality. Also, for Chinese students, to whom I also lecture, understanding better the world is also their goal. I serve as a bridge, and London has been a really good place to do that.

John: What was your inspiration? When did you have your aha moment that you said, I want to start putting my thoughts into this wonderful book, ‘The New China Playbook: Beyond Socialism & Capitalism’.

Dr. Keyu: It was in the thoughts for a while, but it became apparent that there was such a deep misunderstanding about China from the most important country in the world, and indeed, the West. The media consistently reporting just negative news seemed to be so biased, given that this is a country, for all its faults and challenges, that in all of human history has grown the fastest for the longest period of time. And this is a bigger feat than, I’d say, the likes of Singapore or Japan, which are also economic champions, because it’s a massive country. How many large countries of that size have grown that fast, are actually rich, are actually technologically advanced? So clearly something has gone right. I think it’s important to understand that reality. Actually, that was before COVID. I started writing COVID. Now fast forward a few years, now the China model is actually secretly emulated around the world. If you look at Jake Sullivan’s Brookings speech on how to revive American competitiveness, that’s the China model. The return [inaudible] industrial policies, state mobilization, resources. If you look at academic work, one of the hottest topics is new deliberations about industrial policy. Why? It’s because of China, because of China’s success. China managed to build an EV sector, the largest, most productive in the world, within 10 years, not to mention batteries and solar, and so forth. So clearly now they understand that there are certain lessons to distill, but more importantly, I think it’s just so highly imbalanced, this debate, and it’s become very dangerous. That’s why I wanted to write the book, because using data, using facts, using this wonderful wealth of scholarly works that have been done by so many researchers, economists, and political scientists in the last couple of decades, let’s update ourselves on the China model. Let’s not only be discussing the old stuff all the time. In the past, it was manipulating exchange rates, it was suppressing the private sector, it was massive current account surplus. It was all these things. China moves on very quickly. The companies, the sectors, the economic booms, and the trends, it’s very fast. A lot of the old problems are not that relevant anymore. Of course, there are new problems, which I also highlight, but they’re different from the ones that are highlighted in the Western media. It’s fine to be critical of China; we all should. We all should be critical of each other. That’s the great thing about Western school thought: being critical, being self-critical, but at least be critical of the right things. That’s when the discussions are relevant. That’s actually when the Chinese are more able, more likely to accept some of the criticisms to further engage in productive discussion. If you’re always pointing to the wrong things, then they’re just talking past each other and talking at each other rather than talking with each other.

John: Yeah, that’s absolutely right. I want to talk about where we are right now, but before we do that, I want to go through some of the major themes in your book. You talk in the book about incremental progress versus a master plan. Can you share a little bit about your thought process with regards to that?

Dr. Keyu: One thing that people misunderstand the most about the China model is that they think everything is so centralized. It is not the Soviet Union where you have central bureaucracies; all the ministries are tasked with something, and they implement it. Actually, it’s quite the opposite. It’s political centralization and economic decentralization. So, very economically autonomous at the local level. I wrote this chapter called ‘The Mayor Economy’.

John: I love that.

Dr. Keyu: It explains a lot of what’s going on in the past and what’s going on now. We have to understand that. Everything is decided at the local level. Strategically, the central government sets the plan: we should do AI, we should be semiconductor, we should go after growth. The local governments are very innovative. They are an entrepreneurial state. They are a developmental state, and they make things happen. All the EVs, it’s local governments. All the batteries, solar panels, local governments. Just to give you an example, solar panels was a desert in China in 2005, nothing. And then the central government set the task: we have to do solar panels. So first there were 13 cities; the mayors started to implement industrial policies for solar, and then it rolled out to 50, 60 cities. If we look at a map of whether it’s innovation, production, or patents, it blossomed. It wasn’t just in Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen, it was everywhere. It was all in these 60, 80 cities. Who made that happen? The mayors. Same thing with EVs. Now, it’s a very important point here. I think that this mayor economy really galvanized these strategic pursuits, emerging strategic technologies, growth, reforms when they were entrepreneurial states. It leads to the other side of the question, which is the bad. Does China really need 80 cities all doing their own EV brands? Maybe part of that is the overcapacity issue, if you will. Maybe there’s too much competition because of that. There’s a host of problems. But without the state stepping in, and if you just leave it to markets, which is what we’re taught in the Western canonical economic school of thought, how long would that have to take? Just look at the U.S.. I think the U.S. is quite behind the EV transition, green transition, and it’s left to the markets to decide. So there’s the good, there’s the bad. But look, the mayor economy is absolutely essential to understanding the Chinese economy.

John: Can you share that amazing story that I’ve heard you share before? I’m going to mess up the name, the Hefei model with the story of NIO? I love that story.

Dr. Keyu: Hefei is not a well-known city around the world. It’s not considered to be a big city in China, although it has 5 million people. It is not big in China and not well-known. It’s not Shenzhen, not Shanghai, not Beijing, but it is one of the most technologically interesting and innovative cities in the world. It has a global quantum avenue, lots of quantum computing. Quantum communications companies are located there. It also has one prominent EV company called NIO, one of the top three in China. The mayor was very entrepreneurial. He tried to gather these really interesting companies and said, “You come here, we’ll give you subsidized land. We’re going to help you coordinate all your financing from banks. We’re going to build an entire supply chain around you: batteries, control systems, whatever you want. If your kid wants to go to a good school, we got it. If your wife wants to find a job, we got it. Anything you want, and move your headquarters here.” They invested a lot of money even into the company. Actually, the quantum company is very interesting because they were going to build a city metro, and instead of doing that, they put money into supporting a quantum company early days that no private sector investor would have found commercially viable. And today, that is one of the leading global quantum companies in the world. Now, I had some questions about why they didn’t do the metro, but putting that aside, that’s the kind of spirit. But the most important thing is that it wasn’t just the money. It wasn’t just the money because now the governments are quite constrained. It was everything they did around you to support that ecosystem. When we think about industrial policies, again, a really big topic in the U.S. and Europe, they think it’s just throwing money. It’s not just about throwing money. It’s about the ecosystem. It’s about coordination. It’s about allocation. It’s about mobilization. All these things that are not relevant or are absent in the economic models that we study in the West, because the state is supposed to be this separate agent that only comes in when there are market failures. In China, they jumpstart something new, and Hefei’s government has done so well. By the way, the money they invested, they sold at peak, and they actually made a very handsome profit. Actually, one other example is that Tesla benefited from the Shanghai mayor, I think it was Li Qiang, our current prime minister’s, huge support. Tesla was on the verge of being bankrupt because it couldn’t keep up production, and the Shanghai government gave Tesla free cash. Can you imagine giving an American company free cash, cheap land, and massively supporting the Gigafactory, so that it ramped up production massively within a year? No wonder Elon Musk, despite all the political implications, was quite positive about China, despite everything, because he’s seen them and he’s seen it happen. Who are the decision-makers here? It’s the mayors.

John: The NIO story, they were near the end of their rope, and they became a massive success with how the mayor handled them. Is that not correct?

Dr. Keyu: Yeah, absolutely. The mayor once again saved a company, and now the Saudis are investors and so forth. NIO has challenges. To be honest, the whole EV industry in China has challenges, even though they have great, competitive cars, but there’s so much competition within the country. That’s another thing I wanted to highlight. This is a great model to jumpstart these things, and yes, we got the industry going, but then you have all these companies because, in part, they’re all supported by some city, by some city mayor. If you’re a promising one, if you have no chance, no one’s going to support you. But then there ended up being so many of them, and now there’s a lot of competition. There’s price competition. So the market is going to consolidate at some point. Whether NIO is going to do well or not, we’ll see, but it’s still a very fascinating story.

John: Well, since we’re talking about EVs, it’s always great to draw comparisons, the U.S., of course, which we love to think of ourselves as number one in everything, which is clearly not the case. When it comes to EVs, if I’m not mistaken, in 2025, there’s going to be approximately 12 million EVs that are produced in China? Approximately 1 million in the U.S.? Are my numbers somewhat close?

Dr. Keyu: That’s [inaudible], yeah, something like that.

John: There’s something about the infrastructure in China. There’s somewhere around 10 million charging stations in China now, and about 200,000 charging stations in the U.S.?

Dr. Keyu: Something like that [crosstalk].

John: [inaudible].

Dr. Keyu: Actually, China’s EV penetration is around 60% this year, which is [crosstalk] unbelievable.

John: [inaudible]. I was in China a couple of months back, and I saw at least three BYD showrooms. I saw a lot of EVs on the streets, and I’ve been in a couple of them. I’ll tell you what, it feels like a luxury car when you sit inside it. When you start thinking about the price point, it’s literally incredible that they are able to create such a luxury car feeling at such a competitive price point.

Dr. Keyu: You can be sitting in what feels like a Maybach for [inaudible] [crosstalk] up the cost, [inaudible] in a different [inaudible]. Xiaomi is coming out with these explosive products, and that will be very globally successful as well. China really found an angle here. China invested so much, put in so many resources, investing in internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles without much success, actually. You think about industrial policies that are meant to catch up with the West, those have not been that successful. It’s really the industrial policies in the new fields, in the new green fields, that China has done really well. China’s car industry used to be completely dominated by foreign brands. Now they have really sleek, techy, fun, glamorous designs, and that all happened very quickly. That said, despite the fact that they’re great products, that they are extremely competitive from a price point of view, China is still going to have a lot of problems internationally when they try to sell these cars. This is something that I also repeatedly say in China. Yes, it’s true, we dominate in manufacturing and many aspects of manufacturing EVs, but is the world ready to absorb all this from China? Shouldn’t this be globally distributed? After all, the EV is a global supply chain. Many different countries should be participating because we’re not in an international trading environment that mirrors the 1980s, 1990s, when it was all about efficiency. Whoever produced better and cheaper should be exporting more because that was all about efficiency. We’re no longer in that world. We’re in a world of politics. We’re in a world of [inaudible]. We can praise all these accomplishments, but that doesn’t mean that it’s not going to be a complete uphill battle for Chinese EV companies to try to sell these cars elsewhere.

John: It’s true. For our listeners and viewers who’ve just joined us, we’re extremely honored today to have with us Dr. Keyu Jin. She’s a global economist, a professor of economics, and the author of ‘The New China Playbook’. To find Keyu Jin, you could go to www.keyujin.com. Please buy her book. It’s an amazing read, and it’ll give you a much greater understanding of China and what’s going on over there, so we can all be better at interrelating and doing commerce, doing more business, and making a more interesting life for ourselves by interrelating with our great friends and neighbors over in China. Keyu, explain to me the mayor economy and the interrelationship with what you call, and I don’t know how to pronounce it right, so I’m embarrassed, J-U-G-U-O, the Juguo system? Does the mayor economy roll up into the Juguo system, and therefore, that’s why China has grown from 1.7% of the world economy in ’78 to 17% of the world economy in ’23? Is it because the mayor economy was the fuel behind that, which then the greater system called the Juguo system?

Dr. Keyu: Juguo system is translated as a whole-of-a-nation program.

John: I got you.

Dr. Keyu: [inaudible] The Manhattan Project, [inaudible] Americans, but in our own way, in our own Chinese way. It’s a whole-of-a-nation system that incorporates the central direction, and what is, of course, very unique about China, which is the mayor economy. It’s kind of linking the universities, the industries, the central and local governments, everyone in play. If we think about the Olympic gold medals project, that’s kind of what it is: China wants to reap the most number of Olympic gold medals. I don’t know why it’s so obsessed with that, but it is. So they pour in massive national resources to make that happen. That’s centrally determined but locally implemented. That’s the same system that China is using to achieve technological success. I think the Juguo system, the whole-of-a-nation program, is especially important when it comes to technology, even more than GDP growth, because it’s a big paradox that a country with only 25% of the living standards of advanced economies in the West can do cutting-edge technology. That’s the first time in history, and that [inaudible] has a lot to do with this whole-of-a-nation program. The whole-of-a-nation program has evolved over time from the turbans in Mao’s era to today’s many Silicon Valleys all over China. It’s involved in a similar concept. I think the idea that the nation, the state, plus the private sector will pour in resources to undertake technological advances to reduce vulnerability and choke points in China is, of course, a very important strategic national goal. One of the most important priorities for the country currently.

John: Okay, you’re a very young woman, and obviously brilliant, and have had massive success already at your young age, but I don’t know anyone who’s probably more qualified. Let’s say, if you break up your life, you spent 15 years in China growing up, 15 years in the U.S., and 15 years teaching, 15 years or so, I’m being rough with the numbers, of course, in London. So you’re truly a global citizen, and you have a fascinating outlook, and you’re an expert on things that are right now at maybe their highest tension point ever. If you got into a room privately with Secretary Bessent and Howard Lutnick, and President Trump, and you had a private meeting with them, what would you really share? What would be your greatest value of sharing the biggest misunderstandings that they and other world leaders have of China right now? How can they rethink their approach to China so we all have better outcomes, all of us, both sides?

Dr. Keyu: The first myth that I would like to dispel is that China is really not obsessed with overtaking the U.S.. In fact, that is not China’s chief goal. The fact that China has a lot of people, so nominally it could exceed the U.S.’s economic size, is an important but not really that meaningful thing. It doesn’t mean that China is overtaking the U.S.. China actually quite liked the U.S.-led liberal global order. That’s misconception number two. Why challenge something when you have done so well? The U.S. actually has done much better than what President Trump thinks during these last 40 years. China has grown the fastest during these 40 years of openness, trade, and peace. What is the point of replacing the U.S. in things in which China has actually no interest in doing; the responsibilities? And so, in sum, China’s main aspiration, at least economically, is an aspiration for more prosperity, which it believes is a natural right for every Chinese citizen: the path to greater prosperity and having a better life. So that’s the first thing that we would like to clarify for Washington, DC. The second is there’s vast opportunity and room to negotiate that would benefit both countries. There’s no doubt about that. But one has to understand, first of all, respect each other’s security concerns. Second, understand the limits and the broad contours of what can be discussed. For instance, for the U.S. to demand China change its model of development, where SOEs play a role, the state and private has a hybrid role, that’s not really possible. China’s model actually has worked pretty well for China. Lots of other developing countries actually want to emulate it. For instance, conflating political issues like Taiwan or Hong Kong with trade issues is not something that China is really open to discussing. These are separate issues from China’s perspective. Third is asking China to buy more things or respect more IP. Sure, why not? That’s in the interest of China in the long run anyway. There are lots of things that are in the interest of the U.S. and China. It’s a win-win situation, even though they don’t like to talk about that these days that are true, and protecting intellectual property for American companies. Of course, the Chinese government supports that. You cannot be an innovation nation without proper support for IP and protection. Enforcement is more tricky. It’s a big country. The law is not completely set, implementation, and so on, and so forth. Look, the last thing I’d say is that actually, China and the U.S. are not that different. If you really understand China and Chinese people vis-à-vis the values, family, hard work, meritocracy, competitiveness, wanting to win, wanting to do business and deals, and being very crafty about it, they’re more similar than the Europeans are with the Chinese, even some with other Asian nations. The U.S. and China are very successful for all these reasons. So I think there’s a large scope of areas where they can work with. And also to understand, the next financial crisis comes along. The next global financial crisis comes along. We’re due for financial crisis. It’s been many years, and these things that didn’t happen. You really think that that chairman and the central bank governor are not going to talk to each other? That’s mad, not to mention the military communications to avoid total disaster around the world. Small victories, but common goals.

John: We are where we are today. How can global policymakers, both here in the United States and in China, rethink their approach so we don’t end up in a zero-sum game mentality that, like you said, we have more in common than we have different? So why can’t we create a win-win scenario instead of zero-sum mentality here?

Dr. Keyu: The political sentiment has changed. This is around the world, where the whole zero-sum idea is coming back, and a lot of it is political. What we hear in the newspapers, yes, there have been displaced[?] workers. Yes, there have been inequalities rising and winners and losers, but more because of technology than globalization. But it’s, of course, easier to cast aspersions to the other guy than it’s to blame on some robots or machines. The truth is, technology has led to these distributions of gains and losses, but they blame it on globalization. I don’t know how to think about this. I think that fundamentally, they’re not really at odds with each other. They’re competitive, and actually, they make each other run faster. If you look at the whole AI development, chips development, it’s because you have a rival in your rear mirror that you’re actually innovating even more. This reminds us of the U.S.-Japan competition back in the days, where Japanese took over the chips industry, and then Americans actually took it over because they were threatened by the Japanese. Actually, it’s better in the end for consumers. So having some competition is a good thing. One doesn’t want to always be wasting away in comfort, but I think how to manage the relationship will be very important going forward.

John: An issue like the TikTok issue, if you got to be Solomon, how would you bring everyone into a room and just settle an issue like that, which I find to be borderline, at this point, ridiculous. I have so many friends and relatives that love the technology, and they enjoy it, and then you have, of course, the hyperbolic nonsense that’s thrown around in the media, and things of that such. How do we settle that? Just move on, and not let that continue to be a false narrative that just creates more tension than we should be giving it?

Dr. Keyu: Yeah, there’s a lot of paranoia these days about these kinds of things, privacy issues, and influence. We’re in the digital age. I’m very sure that whatever I have in Google, Facebook, and Twitter are also not perfectly protected. I’ve always thought America was a market for consumers. Consumer surplus mattered the most. It was what most people benefited that really underpinned the American markets and American economy. Why companies are ultimately successful is because consumers like our product. Ironically, the angle has completely changed in China, in the sense that China, the government, is so consumer-focused. Now, it’s all about the people. It’s all about what the people want. They almost care much less about the firms, the companies actually providing new jobs, and they just fervently and obsessively care about what people are thinking. This is one of the big misunderstandings about China. I’ve dealt with many interactive local governments, central government, they only care about social stability, about people being happy, people not complaining, people’s welfare looked after, what they like, and so forth. I find it a really interesting contrast between what American people want and that being underrated. I have to say, however, whatever happens to TikTok in the US, has not caused a huge national debate in China. And so many people ask, is this going to be part of the deal between Trump and President Xi? I don’t think this is really on top of the priority list from the national perspective for China. But again, it’s just that it’s odd in the US, where you have innovation, you have something that the consumers really like, and people are not free to choose to use what a vast majority of people would like to see.

John: Interesting.

Dr. Keyu: I also want to add one thing, which is, at some point, I don’t know if it’s still true, four of the five most downloaded new apps in the US are actually Chinese. OpenAI’s research team, according to others who I’ve spoken to, the majority are Chinese, or Chinese-born, Chinese American, I think Chinese-born. So clearly, they’re actually very integrated in some of the most competitive and contentious parts of the technology and economy.

John: Listen, I’m not on it every day, but I have a TikTok app on my phone. To me, like you just well said, if Amazon or Meta or any of these, they know as much about me as any TikTok does, because the guardrails are somewhat open all over the place at this point. There’s so much going on in terms of blended technologies and information sharing behind the scenes, which create, then, the algorithms that are able to serve us whatever they think our interests are, and things of that such. So I think it’s an overblown issue, but I’m fascinated by your take, and I agree with your take, by the way. Talk a little bit, you mentioned earlier, and I know you’ve discussed it before, and I’ve heard you lecture on it before, the one-child policy. Obviously, as you said at the top of the show, you’re a product of the one-child policy. There were pros and cons to it. Like everything else in this world, there’s pros and cons to everything. Where are we now in China’s history in terms of the next generation? And did the one-child policy, at the end of the day, as you look back now, serve the country well while it was in service, and now it’s moved on to more of an open-child policy?

Dr. Keyu: China was really fearful of an uncontrolled population explosion in the 1970s. Actually, the whole world[?] was desperately fearful of a global [inaudible].

John: That’s right.

Dr. Keyu: So many books were written, but now you have the opposite problem. Now, look at what Elon Musk is doing, solving a global demographic challenge.

John: But if we were to look at South Korea, and then to Japan, and then the dropping birth rates are just abysmal.

Dr. Keyu: Yeah. Somebody estimated the last person that will be born in Japan is somewhere not too far away in the future. That is a very scary thought. As with all things, when China decided it was going to do something, it was going to do it very draconianly and very seriously, and that was the one-child policy. It was radical. I was in school with a thousand classmates per year, and only one of them had a sibling. She was a minority from Xinjiang, Uyghur. So it was really strictly controlled in the urban areas. People abided by that law, especially in the urban areas. In the rural areas, they basically let you have up to the first son because they understood and needed labor, and so that was somewhat of a different issue. I’ve done a lot of work on this. I’ve thought a lot about this, the massive economic and social, clearly social, impact that it has had on society. Still today, it has been enormous, and really unexpected. Economically, having one child changes completely the saving dynamics. We looked at twins that are born, you get to keep your twin if you have one, thankfully, and compare it to people with only one child, massive saving differences. A lot of the high savings rate is explained by the fact that you had fewer children. You have to save more yourself as an adult, because in China, this idea of family altruism, intergenerational altruism, means that young people were taken care of by the parents, but then they supported their parents in old age. And if you had four siblings, you shared that responsibility. So the elders felt more secure. If you have only one child, you have to save more for your own old age, and so forth. So that explains a lot of the economic dynamics. Education, very clearly, you have fewer children, you invest much more in their education. Everybody wanted their only child to be either a dragon or a phoenix. That explains a lot of the huge competitive education dynamics that we’re seeing today, everybody taking tutorials and everybody trying to master. Of course, it had to do with the one-child policy. Actually, a really interesting theory that I’ve just come across is that a lot of the countries that really made it to high-income countries started that path once they started having fewer children. Now, for whatever reason, of course, over time, when you get richer as a country, you have fewer children. But just before that, when there was some shock, some policy, fewer children, that jump-started a higher-income path. Why? Because you invested more per child, given that you have fewer. Also, really interestingly, women, girls, had a fabulous time. I’m born in the golden age of women for China because girls suddenly got the same amount of education as a boy. Actually, girls had a higher return to schooling and did better because they caught up in the gender gap for higher education attainment closed immediately. Now I think it’s even higher. This explains why people born in the 1980s and 1990s, women, occupy such critical positions, especially in the private business community, being real leaders, now actually even going into politics as well. Not at the very, very top, dominated still by men, but even at the ministerial level, very strong Chinese women were brought up in an age where they were treated equally. They were expected to be maybe the Mulans of the family, and they were given as much ambition as boys were. So these are really interesting social consequences, but I think it really did change the dynamics of the social fabric. Also, I think it explains why Chinese people don’t want to have many children now, the younger generation. Number one, education is so expensive because it was a huge competition. Second, housing prices, of course, are high, but also, they had tough childhoods. It was all about studying and about achieving, and a lot of them went through huge [inaudible], now they are angst for the parents as well. One of the most popular TV series in China is about how to get your kid in school. That’s how obsessed the whole country is. And so that angst became a national angst for your child; is he or she going to have a future, is he going to get the right school, the job, all that? It’s become such a national-level point of anxiety that this is when the government came in and cracked down on the education system. So all these things are related to the one-child policy, including many different puzzles like why can 20-year-olds afford a Beijing apartment that is the same price level as a San Francisco apartment, despite having only one-tenth of the income of a San Francisco worker? Why? Because everybody[?] pools their resources; your parents, your grandparents, maybe the spouse’s parents, all pool their resources, six wallets, to help you buy a house. So lots of interesting dynamics there due to the one-child policy.

John: Got you. What’s the worldview of a typical Chinese citizen now? Americans always take a very narrow view. We’re first among equals. We think we’re always number one. The average Chinese citizen today, when they see all the conflicts around the world: Russia, Ukraine, the Middle East conflicts, and other conflicts, and of course, the ongoing tit-for-tat between our presidents right now, some of it overblown. An average Chinese citizen today, what’s their worldview compared to an average American citizen?

Dr. Keyu: First of all, I hate to say it, but the young people in China today do not aspire to have a Western-style democracy. It’s happening around the world. Look, if it really did have a much better track record, or if countries that adopted it and transitioned into it did much better, then I think there would be a serious challenge to the system today, coming from the people, coming from the next generation. But they look at the chaos, they look at the economic consequences, they look at the mess, and rightly or wrongly, they don’t necessarily aspire to that. Some people in China would actually say, “Thank goodness we’re here. At least there’s stability, there’s safety. That for sure.” I can’t vouch for London on safety. But security and a chance for prosperity, even though China’s economic challenges are dim currently, it has affected their expectations. I think that is the biggest downer currently. But in terms of just having the necessities of life, I’d say many of them are actually thankful that they’re in China, given what’s around the world. Again, like I said, if it had been really successful elsewhere, with the Western democracies. I think China’s political system would be in a much bigger threat.

John: Obviously, like I said, you’re a global citizen, and you’re still very young. When you start thinking the next cycle, what’s the biggest challenge facing China right now for the next 5 years, if you were to just take a five-year snapshot? And then when you think out 50 years, what’s the biggest challenge of China for the next 50 years that you’re thinking of?

Dr. Keyu: First of all, if you ask me if I wish China had a more free and open society, the question is absolutely yes. These are elements that the youth will be seeking as well. So I’m not denying that the good things about open democracies are not there. They’re there, but lots of things have improved, and one thing, government accountability to the people is actually strikingly remarkable compared to my experience in Europe, for instance, and probably what it is like in the US. The fact that local governments really care about the welfare of people, from the environment to, let’s say, if there was a natural disaster, to the economic challenges of today, to protecting them against data exploitation, scams, and all that, and making sure that they have security and safety. They’ve done a pretty good job, and if you look at the system, the process, it’s been very open. You can make complaints against the local government officials online, and that will be sent to the central government, and so forth. So there’s a real interest in protecting the people. In some ways, it might also tend towards a bit too much. For the sake of the economy, for the sake of the balance, it’s a little bit too balanced towards the people. We see that in lots of populist agendas as well, not for re-election, but just because this current government wants to mostly put their attention on the people. So in that sense, it’s improved a lot, and there are lots of things evolving over time. So if you were asking about the next 5 years, I think getting out of this economic slump is absolutely pivotal. It’s about expectations. I always say this to people, it’s not about political rights at this very moment that every Chinese person and Chinese family is thinking about. It is quite practical. It is about, “Is my son going to have a good job after all the resources I poured into educating him? Is he going to be able to have a family since the housing prices are so high? Are we really actually going to have rosier future expectations?” That’s what they’re thinking about, and that’s current. In the next 5 years, China has to get out of this economic slump. I disagree with a lot of the policies that are implemented. I wish there was more that would be done. Maybe it is not wishful thinking; I think it will happen, but that’s most critical. In the next 50 years, the world is changing so fast. Is there going to be political evolution? I think there is. I think we’ll be very surprised by what’s going to happen in the next few years, politically speaking. The new generation, which I wrote about a lot in the book, ‘The New China Playbook’, they’re very different from my parents’ generation, risk-averse, pragmatic, kind of savers. They are buyers[?]. They are political participants, they are connected around the world, they care about social values around the world. They’re quite sensitive, politically sensitive as well. So they will demand changes. But maybe not quite the path that the West sees. Something will happen; something will evolve, but if we look around the world and how many countries have that kind of stability of environment and opportunities where the next generation will be doing better than our generation, very few around the world.

John: Do you continue to remain hopeful that we could all borrow the best practices from each other and coexist, instead of making a zero-sum game and wanting to vanquish the others? Do you feel hopeful in the months and years ahead, with the political changes that you’re saying could happen in a very positive way, that your approach of mixing approaches, and not just taking a dogmatic approach to government and economic innovation and things of that sort is possible for all of us, both China, the US, and far beyond our two countries?

Dr. Keyu: I am hopeful, because that’s really the only path. We’re not going back [inaudible] the jungle. [inaudible] despite our frustrations, and all the bad things that we read in the media, the world has become a much better place. Reduction in violence, improvement in human development [crosstalk] indicators [inaudible] around the world. That’s the fact, and people at the micro level see it. That’s based on this concept that it is win-win, that it does depend on peace and prosperity, and countries do work together. Despite what maybe one president, one administration might think, look at what’s going on around the world. They’re setting up more trade agreements, more alliances, more diversification, more investment partnerships, more regionalism, more resilience all around the world. Premier[?] Li said we’re going to unilaterally lower tariffs to zero for the least developing countries. Clearly, I think the rational, empathetic, human, embodying human values, that group of people outweighs the more erratic, more politically driven people in the world. Look, is there an alternative path to coexistence between the U.S. and China? Absolutely not. It would be faster all around. [inaudible] we have to figure it out. But there are enough smart people, enough sane-minded people in [inaudible].

John: [inaudible]. That’s right. I hope this is not a fever dream of mine, but I saw videos, it was not President Xi, an exchange student himself, and lived part of the time in Iowa or somewhere. He has unbelievably warm and kind things to say, not only about his host family, but his education in America and the American system. He said, “Listen,” this is what I understood, at least, and I took away, but please correct me if I’m wrong. “If I was born in America, I would enjoy playing in their system as well and championing that system. I was born in China, and of course, China’s home. This is the way that I feel is the best path forward for our country.” He has put out an olive branch and said so many kind things about our country that, gosh, I just couldn’t see how it wouldn’t be an enjoyable experience to be with him in a room, trying to figure this out rationally, rather than lobbying some of the hyperbolic talk that goes out and probably gets exploited and overblown by the media around the world.

Dr. Keyu: Yeah, media is politically charged, emotionally charged, whereas the reality lies with the people, the people-to-people connection. The rivalry is not from person to person. The academic exchanges, the knowledge flows, the scientists, the doctors that communicate, actually, the Chinese and Americans make great partners because they’re going to do the best business. It’s unfortunate that they’re forced not to do business with each other, but there are so many similarities. I think President Xi was very genuine about what he said. I also spent a lot of time in the U.S. I see the awesome things in the U.S., and I also see the awesome things in China, but we have to recognize that China and the U.S. are different on some levels: the history, the culture, the legacies. They can’t look identical in all these things. So I think, sitting down, having that personal touch, but really also doing what’s right for your people. Ultimately, the vast majority of people, not for one small industry, tens of thousands of people, but for the vast majority of consumers, doing what’s best for them. If we operate based on that basis, even if we don’t talk about win-win, it is win-win in the end.

John: It’s just fascinating. I’m also fascinated by the shift from it used to be our politicians were our heroes in America. It’s now a lot of the Silicon Valley folks. If we look at Silicon Valley, the second-richest man in the world is Larry Ellison. He’s married to a Chinese woman. And of course, Mark Zuckerberg is married to a very accomplished Harvard doctor and again, a Chinese woman. So to me, there’s going to be a bridge, and maybe Silicon Valley is going to lead the way on the bridge. Talk a little bit about yourself. Obviously, like I shared, you’re brilliant. You’re still very young. You’re a global citizen who spent a third of her life in three different areas: the U.S., China, and London. What’s the future hold for you? You’re a professor, you’re an expert in some very important skills that we desperately need today to make the world a better place. Plus, you’re also an accomplished author, and I encourage everyone to buy your wonderful book. I’ve read your book; my friends have read your book. This is a very valuable book for anyone who wants to understand China, and even understand the United States better. What’s the future hold for you? What do you love doing the most? And what are you going to pursue now that you have another 50 or so, or more, wonderful years on this planet?

Dr. Keyu: I’m not that young, given that you’ve said all the years I spend one place to another [crosstalk].

John: You’re still a lot younger than me. So you’re young.

Dr. Keyu: Very uncharacteristically Chinese, I’m not thinking about the future too much. I’m actually quite living in the present and working in the present. I’m going to write more books, communicate lots of things. There are so many important things I want to write about and want to share with the world, share with the Chinese, share with Americans. In my own particular way, joining the forces of many others who have been bridges of various sorts to help communicate between the two large powers and the rest of the world. You are playing a very important role, and in the small ways where we can have an impact, that would be already enormous. And spending time with my kids, enjoying nature, enjoying my music, and just trying to be happy every day.

John: What’s on your heart, though? Like every other creative and every other artist, when you’re a writer, you’re a creative. What’s on your heart in terms of writing? What’s the next topic you want to write about that you believe your voice has something important to share with the world?

Dr. Keyu: One project that I am working on is a return to localism from globalism, and how that’s an inevitable trend, but in a very good way. It’s anchored in globalism, but a return to the local identities, the local companies, local cultures, not needing the certification of, let’s say, the Western recognition to be confident in all things from kind of economics, companies, fashion, technology, film. I see that happening. So what’s in the post-globe world is what I’m really interested in as well.

John: Understood. And you’re not going to give up teaching, I take it? You’re going to still teach?

Dr. Keyu: I’m going to teach a bit. I’m going to teach selectively.

John: How about commercial? Do you see yourself advising more on commercial ventures, such as big corporations, and how to navigate a more politically charged world? Or would you rather advise the politicians themselves? Where does your love and where does your heart fall with regards to who and how to advise?

Dr. Keyu: Wherever I can make a difference. Currently, I’m doing both. I sit on boards of global luxury companies, but also global conglomerates, and advise some governments on how to think about and implement their future vision, given that we’re in such a wildly volatile world. I really enjoy both. I do enjoy learning, being so grounded, and then connecting with all things here and making sense of each other.

John: You dedicated this book to your parents. Talk about your parents. Are they still alive and with us?

Dr. Keyu: Yes, they’re very well. They are enjoying time with my kids. Again, like all Chinese children, we are very close to our parents, especially in the one-child policy, despite the many scoldings, the many disciplines, the tiger mothers, and all these things that my American friends were just totally shocked by. The authoritarian parity. Despite all that, we have a very close bond, like many other Chinese families, so of course, there’s [inaudible].

John: Your dad was quite famous. Was your mom a tiger mom?

Dr. Keyu: In her own way. I think it’s important to create the love and passion for something, and my father did that with all his love and passion for Shakespeare and books, and learning in general.

John: What’s your generation of brilliant moms called now? Do you want to be known as a tiger mom, or is there a whole new terminology with your generation?

Dr. Keyu: My generation of moms, probably more sheepish than tiger moms, [inaudible], maybe they don’t want to impose all the burdens they’ve experienced when they were children. By the way, that’s not at all how I think. I want to be still distilling the best of the Eastern education and the Western education. I really think the optimal lies somewhere in between, that the discipline, the skills that you develop under the Chinese system, has to be in conjunction with the space that you’re given to be more creative. And, of course, most importantly, to have a sustained, lifelong yearning for learning, which is what the American education really fosters very well. But in order to have these achievements, you also need the physical and mental capacity to carry them out. That is what the Chinese education prepares you for. We can talk a lot about STEM, but really, these kinds of basic foundational skills are still really important, even in the age of ChatGPT.

John: That’s wonderful. First of all, thank you for the generosity of your time and wisdom. You’re beyond brilliant. The only thing I regret is I wish there were 50 more of you on this planet to just smooth things out and make the world a better place. We need more people like you to advise our leaders, both in business and in politics. She’s Dr. Keyu Jin. This is her book, ‘The New China Playbook: Beyond Socialism & Capitalism’. You can find her at www.keyujin.com. You can buy this book on Amazon.com and, of course, barnesandnoble.com and any great bookstore around the world. Thank you for your time. Thank you for everything that you do, and just thank you for making the world a better place.

Dr. Keyu: Thank you so much, John. It’s been a huge pleasure to talk to you. Thanks again.

John: This edition of the Impact Podcast is brought to you by Engage. Engage is a digital booking platform revolutionizing the talent booking industry. With thousands of athletes, celebrities, entrepreneurs, and business leaders, Engage is the go-to spot for booking talent for speeches, custom experiences, live streams, and much more. For more information on Engage or to book talent today, visit letsengage.com. This edition of the Impact Podcast is brought to you by ERI. ERI has a mission to protect people, the planet, and your privacy, and is the largest fully integrated IT and electronics asset disposition provider and cybersecurity-focused hardware destruction company in the United States, and maybe even the world. For more information on how ERI can help your business properly dispose of outdated electronic hardware devices, please visit eridirect.com.