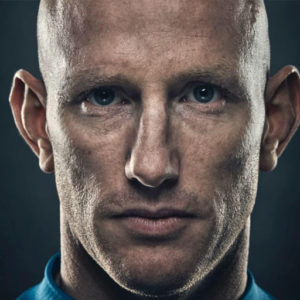

A former British Special Forces Soldier, 2x World Record Holder, Adventurer, Philanthropist, Author and International Speaker.

After making it through the Special Forces grueling 6 month selection process, Dean became one of the very first army members to join the SBS (Special Boat Service). Throughout his esteemed military career, he has conducted deployments to overseas hostile environments and been involved in Counter Terrorism operations; he has travelled to some of the toughest places in the world.

Dean left the military in 2011, after 16 honorable years of service but continues to live by the Special Forces’ ethos of ‘the unrelenting pursuit of excellence’. The determination required throughout his career has become an integral part of Dean’s character.

He then established a distinguished career in the private security sector; he was renowned for his willing to take on any job, no matter how dangerous. The man who went, when others won’t. He has faced extortion, kidnapping, civil war, pirates, military coups and was single handedly responsible for the evacuation of the Canadian embassy in 2014 rescuing 4 diplomats and 18 military personnel.

John Shegerian: This edition of the Impact podcast is brought to you by Engage. Engage is a digital booking engine revolutionizing the talent booking industry. With hundreds of athletes, entrepreneurs, speakers, and business leaders, Engage is the go-to spot for booking talent for your next event. For more information, please visit letsengage.com.

John: Welcome to another edition, the veteran’s days special day edition of the Impact Podcast. This is truly a special edition, it is thirty-two years in the making. I will get into it why in a second, but we have got the ultimate veteran badass with us today. He is an adventurer, explorer, entrepreneur, philanthropist, and author. That is what we are going to be talking about today, I got his book right here, I have read it twice actually. We have got Dean Stott, welcome to the Impact Podcast Dean Stott.

Dean Stott: Thank you very much, John. I appreciate you having me.

John: This is an honor, and thank you for being with us. Dean, before I get asking you questions about your fascinating and truly inspiring journey, both in the military and outside of the military, can you share your background a little bit? Just teeing up in terms of military family, get it going into the military, becoming basically one of the top people in the world with regards to skillsets and what you accomplished there and then after the military. Give a little bit of your bio first.

Dean: Of course, I will probably start in the beginning. As you mentioned, I was born into a military family myself. My father was in the military, both my grandparents were in the military as well. So I grew up in a town called Aldershot which in the UK, is a home in the British Army. I was immersed in that military environment. When I went to school, the airborne regiment used to parachute into our field. It was not strange to see helicopters flying over to schools and guys jumping out of the skies. So I am very much immersed in that environment and as a young boy, I always wanted to be a fireman, always wanted to be a firefighter. When I got to the age of seventeen, I left school and there was not really much employment going on, so I thought well maybe the military is a potential option for me. I approached my father and I told him of my intentions. He gave me those warm comforting words over the last two minutes. Probably was not the response I was actually expecting but at nine and a half stone and 5 foot 7 inches, I could probably see where he was coming from. I generally believe there is no point in arguing with someone until you are blue in the face. I just thought well, I will go away and I will prove him wrong. I did that, I joined the military at seventeen. My father was in role engineers and I also joined in role engineers as well to get a trade and something back. By the age of twenty-one, I was a para commando diver at PTI. I have done every arduous course in the role engineers that was open to me. The only other path for me then was UK Special Forces. I had pretty much put the bed any doubts of my father that I would last two minutes. But coming from an army background, the normal transition for us is the Special Air Service. But the Special Boat Service had just opened their doors up tri-service. Prior to that, you had to be marines. It is one hundred percent marines. I applied for UK Special forces selection for the Special Boat Service. So just your listeners are aware, the course is exactly the same. The SAS and the SBS do the same six-month course together. So much to the disgust of my friend in the army, in the SAS, I went down the SBS route and I was fortunate, six months later, to be selected and became one of the first army guys ever to go Special Boat Service. I think now fifteen years on, something like fifteen to twenty percent of the SBS are now army recruits. So, being one of the first is what opened those flood gates. But again, it sort of goes with that theme that if you tell me I cannot do it, it just gives me more fire in my belly to prove you wrong.

John: One of the themes in your great book, and again this book is just amazing for our listeners and now viewers out there, Dean Stott’s Relentless from SBS to world-record breaker. And I have marked this book up and I have written all over it and one of the important themes I took out of this Dean, you tell me if I am wrong, when people tell you you cannot and they put a chip on your shoulder, you take a chip, you make it a boulder on your shoulder and then you proceed.

Dean: Yes.

John: You literally take that chip and you make it much bigger than it is in your mind and you lean in, and you go.

Dean: Yes, I do not take it personally. People always try to compare you either to themselves or people they have seen in the past, but you are unique. You are one on a kind. There is no point of you trying to sit there and argue with him and prove them wrong verbally. The best way to do it is through action. Just take on board what they said and use that as almost fire and energy. That negative energy are then turned into positive energy and when it does get a bit hard, you always remember what they were saying. Then you come back successful and you do not need to say anything. Your actions just spoke volumes.

John: For our listeners out there that want to find Dean, that want to have him speak at one of their events, or buy his book on Amazon or Audible, you go to www.deanstott.com. Dean, talk a little bit about your experiences in the military and really the badass stuff you are doing. I am going to a page in a book which comes down to just life. I love this line here that you said in terms of some of the tighter moments you got into why you are in the military, this sentence here, “My call when it comes down to it, the biggest moments in your life always are.” The accountability and the personal accountability that you take for everything you do, “My call.” There is a whole book to be written just on that issue. Talk a little bit about your experiences and how you made the right decisions most of the time during your military experience.

Dean: I think the reason we are one of the best militaries in the world, the Special Forces, is because we are always learning from our mistakes. Not because we are the best caliber and the best training, so we are always in these various scenarios. I always believe you cannot be experienced without experiences. Obviously, some of those situations maybe early on in my career, I would make the wrong call but I had learned from that and then I would never make that mistake again. The accountability is the big one. I know the story that you are referring to there. I was in a situation where I was dressed up as a local Taliban in Kandahar and I had missed– obviously I am getting too much there, I had misread the situation. But it was on my call, I thought I have been compromised and there was a threat from the general public. What was great about that is obviously, talking back to HQ through the radio is on your call. They cannot question your decision because they are not in your seat. You are the only person in that position. You got the atmospherics, you are feeling[?] the pressures, you know that you should not be there. That is why I always say you need to step back and look in. A lot of people rush in and make the wrong decision. I think that is what I did to that and thankfully, I then found out they were making me aware that my turban was stuck in the door, whereas actually, I just misinterpret the whole scenario. But should I had made the wrong decision, I am accountable for my decision but that was what saw on the ground and that was how I read it. No one else back in the UK or back in HQ could question my decision and that is the reason why we go through such arduous training, because you are making key decisions which can have really bad consequences if gone wrong.

John: Talk a little bit about your experiences in the military, other experiences. You were involved with counterterrorism and all sorts of fascinating situations, how long was your career in the military? And share a couple of your favorite anecdotes.

Dean: I joined the military at seventeen. When I joined the Special Forces at the age of twenty-eight, I joined at the height of war and terror. It was the busiest time of the UK Special Forces. I was out in the Middle East on operations, I would be diving off cartel boats in Columbia, or I would be rescuing hostages at the East Coast of Africa. I was literally living and breathing what these children out there are playing, Call of Duty. That was sort of my lifestyle. Obviously, because of security reasons, I cannot go into too much detail on some of the operations, but it was very vast. I did sixteen years in total. Whether it was in the Special Forces, whether it was in the military, everything I just enjoyed it. What I really took away from the military, we talked about the unrelenting pursuit of excellence that if you are going to do something, you do it to the best of your ability. Which is think is a great force[?]. It is not just in military or school, it could be in anything you do. Whether you are a carpenter, whether you are an accountant, you just give it your one-hundred percent. I did enjoy the humor. The military have a very dark sense of humor and I think you need to have a dark sense of humor because you are in certain scenarios and situations in which if you took it too seriously, it would play on your mind mentally, so I have in that. But my father, as I mentioned, is a big part of my life. When he was in the military, he was the army soccer coach and manager. He was very competitive and I had a very competitive streak from him and I had love that about the military. I did not feel threatened by others, but I was just competing internally against others, and you are in a great environment with other competitors, other athletes as well, so yes I really soaked up. I generally thought I would only do about two or three years in the military. I then sixteen years later, at forty, I had to leave prematurely because of the parachuting accident.

John: Share a little bit about that crazy accident because it bears discussing. You had to overcome a lot just to survive the problem that happened when you were jumping out of that airplane.

Dean: Yes. We were due to go back out to Afghanistan and we were on pre-deployment training out in Oman and we were doing what is called a HAHO Jump, a High Altitude High Opening Jump, which is a method of insertion that we used. I think it was the third or fourth jump of the day and I had done hundreds of these jumps before. You exit the aircraft at 15,000 feet so you are on the limits of oxygen. Then the parachute opened straight away. I mean you travel up to 50 kilometers or thirty minutes flying time in the air to get to your designated area.

John: Wow!

Dean: It is just normal procedure. I did, I believe, the fourth jump of the day. Exited the aircraft and unlike the other jumps, my legs got blown up above my head as I exited the aircraft and my leg got caught in the line above my head. So my first concern was to clear the legging time before the parachute opened. I could not free it in time and then the parachute went top and opened behind me. My leg got pulled up over my head into the right and thankfully my leg did release. If it did not, it could have come completely off. Just straight away with the pain, I knew there was a problem. The pain was that severe that I was vomiting through the pain. But because of the altitude, I was also drifting in and out of consciousness. The rest of the team were unaware that there was a situation at this point, so my first concern was to stay with the team, get to the descent[?] but also land it. Because you have got one bad leg and you need to try and land it well. There is obviously risk of damaging the other leg.

John: Right.

Dean: I approached the descent, I saw the approach of the other parachutist and I have gauged the winds correctly and I landed perfectly on one leg but unfortunately, the damage sustained ended my career. I tore my ACL, my MCL, and my lateral meniscus within the knee.

John: Oh!

Dean: My hamstring, my quad, and my calf muscle as well. So all the supporting muscles around the knee as well. Unfortunately, after sixteen years, that was the end of my career. Now in reflection looking back, that was a big period in my life, probably a dark period in my life. Everything I had known from a young boy growing up in that military environment and then joining the military itself. The military is very good, they are like your mother and father. They clothe you, they feed you, they pay you on time. You do not care what sort of tax you are paying, you are just doing the job that you love. To then sort of be told, “Thank you for your service, you are no longer required.” I went through what is known as an identity crisis. You have gone from working in a tight-knit unit and a team, part of a tribe, and then basically told to leave. And how do I now fit in society? What are my skillsets? Where is my role or purpose? That was the first obstacle I had to overcome.

John: Let us go back to that injury. I do not want to just overlook that injury. Any of the things you just mentioned on their own is a very very bad deal, meniscus tear, ACL full tear, you had compounded injuries to your leg which I just wanted to review here because when we go on to some of your other massive and beyond-inspiring accomplishments, I do not want to overlook. How long did it take you to get well just from your injuries?

Dean: Initially, it was the same time as the volcanic ash from Iceland which had just shut down all air traffic globally. I was in Oman. The gold scenario would be to fly straight back to UK and start physio straight away because there is a chance that you can rebuild it. You see rugby players who tear ACLs but continued playing, but obviously, they have their other supporting muscles, which I did not have.

John: Right.

Dean: My first obstacle, I had four weeks in a hotel in Oman just on painkillers because there was no flights available to get me home. I finally got back to UK, I think it was about six weeks later. I got to the hospital, already you can see the muscle wastage in the leg, got sent home, came back another six weeks later. They then lost my MRI scans and there was then a spiral of other medical issues. It actually took me forty-four weeks before I got operated on.

John: Forty-four weeks after the accident?

Dean: Forty-four weeks after the accident. I tore my lateral meniscus probably about eight years before and I was operated on within seventy-two hours and back running. Just tells you the difference, you know the scale. So that obviously contributed to obviously me leaving as well. Which was sad really because I do love the military, I love promoting the military. You almost left under a bit of a dark cloud, the fact that your medical was neglected. But for me, I just picked myself up and we just carried on.

John: Was it harder for the doctors to help you? If they had operated much sooner, post-accident, versus forty-four weeks, would have things gone easier and better for you just personally?

Dean: Yes, potentially I may still be in. You never know.

John: You never know. Okay, so now you are out. You are out of the bubble, the tribe, what you were used to for all those years. You are out of the military and now you had to find a new way.

Dean: Yes, I had to find myself. Also, to add to the pressure, my wife was also eight months pregnant. So not only are you stepping into a new world, my wife was eight months pregnant. You hear stories of people transitioning to civilians. Some can be quite smooth, some can be quite turbulent. Now thankfully for me, mine was quite smooth. My life is very entrepreneurial. Last year she was a runner up Businesswoman Entrepreneur of the Year UK.

John: Wow!

Dean: She was a bank manager running a few banks when I met her. She set out my first security company on her blackberry watching tv. For me, I think it was like three months of paperwork. She took away a lot of those, potentially, additional pressures that were put on me and my focus was just to try and find work. But yes, with her being eight months pregnant, I did not know whether if there was any work out there and if there is plenty of work anyway. Without sounding like Liam Neeson, people with our skill sets our natural progression is the private security sector. So it was a natural step for me.

John: [laughter].

Dean: Within forty-eight hours, I was out in Libya in Benghazi during the height of the Arab Spring in May 2011. Gaddafi was now in Tripoli. He had been corded. But as soon as I hit the ground in Libya, I soon identified that the Libyans did not want it being another repeat of Afghanistan or Iraq. Once Gaddafi had fallen, they wanted to take control of their country. They did not want private security companies walking around with weapons, etcetera. Also, I was chatting with some of the big private security companies and they were charging six figures sums to these crisis managements and evacuation plans for NGOs for the oil and gas sectors, and MNLs, but when I started scraping the surface, I soon identified that there was actually nothing in place itself. So that got the cogs going in my head. You know for me, I wanted to find a niche within the industry. I did not want to just work with private security companies. With my sort of mindset, I wanted to strive to be the best that I can be. So I flew home two weeks later, my wife gave birth to our daughter Mollie and I said, “Look, do you mind if I take some life savings out of the account?” and she said “Yeah, what is your thoughts?” So I told her. So I flew back into Libya and I bought thirty weapons on the black market, because there was a huge proliferation of weapons at this point. I just buried them between Tunis and Egypt and spent a month on my own in the desert just right to my own evacuation plans, burying weapons, communications kit, and money. That is what I did, I then sold it to some of the oil and gas sectors and just monitored that. My sort of main passion or my main drive within the private security sector was the corporate industry, it was the closed protection. The great thing about the security industry is very similar to the military. When you tell people you are in the security industry, I think they think that you are a doorman from the local nightclub. It is a very diverse sector as well.

John: Right.

Dean: Surveillance, closed-protection, coaching, or mentoring, there are a lot. Every time I got a phone call, it was a different job. Whether it was taking UAE world family superyacht from Barcelona to Maldives, whether it was training the Curtis Special Forces to fight ISIS, and the next phone call would be to go to the World Cup in Brazil. It was a great industry and I was enjoying it. I just finished the London Olympics in 2012, and I was out in Libya again in Benghazi and it was September 11th, 2012 and it was the evening that the American ambassador that got killed in Benghazi. I think they made a film called 13 Hours.

John: Right.

Dean: I do not know if it was the right place, right time or wrong place, wrong time. But I was in the city that evening and I was asked if I could help a German oil company get their engineers safely back to Tripoli. So I got eight German engineers safely through safehouses that I had in the desert and gotten home safely. Because of the success of that, two years later, I was in Brazil covering the World Cup and it was called the Tripoli War. It is a civil war between the military and the government, which is still ongoing at the moment, I got a phone call that the Canadian embassy were now stuck in Tripoli and could not get out. And my name kept coming up, they said “This is the guy you need to speak to.” And I work on my own. Everything I do, I work on my own. So I flew back in, had a great fixer and I came in and just sat down with him and I helped and planned and got them out. So I singlehandedly evacuated the Canadian embassy, eighteen military and four diplomats from Libya to Tunisia. It sounds very sexy and it sounds very Hollywood, but actually, I have never had to dig up any of my weapons. They are all in position. The actual success of this was understanding the political inferences, the tribal inferences, the demographics of the country. Not going in with a lot of the guys and loaded weapons and just pulling our way through, it is actually all about communication. Speaking to the right people, letting them know our intentions. So the British embassy, the week before, got shot at at every checkpoint that they have gone through, which obviously was spooking the Canadians. So, myself and my fixer went out, we did not speak to the guards, we spoke to the tribal elders responsible for that region. Actually, it was all about communication and respect. Just letting them know who we are, that we were no threat, and what our intentions were. And that is pretty much my approach in the private security sector. It is not about being passive-aggressive in image, it is about having respect, and being more discreet and being non-intrusive, but just keeping those lines of communication open.

John: Dean, a couple of things, first of all, it does sound Hollywood but it also sounds fantastically dangerous.

Dean: Yes.

John: It sounds very dangerous. Is this called– I mean help me out, this is again, from my Hollywood knowledge and also some friends, is that what is called a Hot Extraction?

Dean: Yes, it can be called a Hot Extraction. But for me, this is when the pin dropped for the second time for me. I came home from this trip and I had blood on my shirt and I said to my wife, my normal procedure when I got home was to wash my clothes, repack my clothes ready for the next phone call. And I said to my wife, “Can we get the blood out of my shirt?” I had blood on my shirt because I was administering first aid on an RTA, a Road Traffic Accident at the border. And my wife said, “Yes we can get the blood out, but I am more intrigued in how the blood was there.”

John: [laugher].

Dean: I told her what I have just done and she sat back and said, “Have you heard yourself?” You know for me, it was almost a throwaway comment that I just evacuated the Canadian– but that was my life at this point. But the pin dropped when my wife then highlighted, I have only been home twenty-one days in a three-hundred and sixty-five-day calendar. You know chapter sixteen in the book is called Dead or Divorce and I think that is where we are here. What it was is I was actually trying to match the adrenaline rush I had when I was still in the Special Forces.

John: Right.

Dean: Without having to come to terms mentally that you were no longer in that group. You no longer have that support network above you, the government, the helicopters, the aircraft. So yes, that was a real realizer for me. But I just got so immersed in working in those countries, Somalia, Yemen, Libya, and I just felt comfortable in those countries when in fact now looking back, yes it was quite dangerous.

John: Before we get on, for our listeners out there who have just joined us, We have got Dean Stott with us. He is a veteran of the British Special Forces. He is an adventurer, explorer, entrepreneur, philanthropist, and he is an author of this amazing book. Look at how many places I have marked it up here. I am so fascinated, there is so many things I need to ask him about and I bought a couple cases from my company and for our listeners out there. This book has so much in it for everybody. You could it on Amazon, you could find it on Audible, also on www.deanstott.com. You know, Dead or Divorced, one of the themes to this great book and you actually had a line on your book that said, “No man is an island.” Your wife Alana has been not only your cheerleader and supporter.

Dean: Yes.

John: She is your teammate. On almost every chapter she shows up. Whether through encouragement or coming up with as you said, a business model post-military, the support. We are going to talk about her throwing a Guinness Book of World records in your lap in a minute or so, but finding that rush that you were so used to with that whole military around you in the private sector, it was a quest that is so fascinating and I think that you are still on it. You are a very young man still which is the fun part of your life. But your wife is truly a special human being and been a heck of a partner and I think that should not get lost in the messaging here in that anyone to accomplish the greatness you have, the fact that you chose such a wonderful person to be your partner I think is such an important message that our listeners hear out there. So anyway, hats off to your wife Alana. I hope I get to meet her one day, but man, she shows up in this book in so many ways and is such a huge support of yours. I am so impressed by how you guys have operated as a team to succeed over and over again.

Dean: No, I think I am very fortunate. Like I said, I felt there was a void when I left the military being in a tight-knit unit, and a team. And then actually then found it closer to home. It was actually here all the time. It was just I was not aware of it. As I have mentioned, Alana is very entrepreneurial. Anyone who knows us as a family knows that basically, Alana is the one behind the driving. She is the one who is managing everything. We know our strengths and weaknesses. Mine is more of the physical and Alana is very much more of the mental.

John: That is okay.

Dean: Yes.

John: You got it both covered. So now, on to the next mission.

Dean: Yes.

John: Pursuing in a relentless way excellence and being relentless in your pursuit of excellence and that adrenal rush, talk a little bit about how you and Alana came up with the most fascinating Pan-American highway challenge that you created and you obviously killed. I want you to share the whole story behind the story.

Dean: Obviously, after the Canadian embassy, and Alana and I chatted, we then soon realized that it was actually lack of communication between ourselves. She thought I wanted to go away all the time and I thought that she needed me to go away to bring in the money. Alana was now a property developer and she said, “Well, no I do not need you to go away, we are very comfortable back home. Why do not you just hang up your boots for a bit and do that?” So I thought “Perfect! I will do that, why not?” And during this whole period, it is probably five years now from the injury to where we are at this stage. I neglected my own physical and mental wellbeing because I have been so fixated on the work, just working and helping others. My injured leg was now two kilos lighter than my good leg because of the muscle wastage. I decided to buy a push bike and just cycle to and from the office. There is only about eight miles there and eight miles back and I thought, “Well perfect!” But straight away, just being active again, I felt a huge weight off my shoulders. Where I got to in the military is because of my physical attributes, that had been taken away from me, that I could not run anymore. Actually being on a bike, I felt like doing some sort of cardiovascular, I felt a lot better. I just cycle to and from the office and I spent a month with Alana doing this property development. You can imagine with my backstory, sat with these architects and planners meetings, I was not really interested in the plumbing system. It was more of the coffee and the biscuits.

John: [laughter].

Dean: Alana could see that glaze over my eyes, you need to do something. But obviously not smuggling people across borders. So, it was about a month before my fortieth birthday and as a young child, I always read the Guinness Book of Records. I was always fascinated in these people’s feats. And I said, “Well I have always fancied doing a record.” And she said, “Well what end?” And I said, “Well why not cycling?” Cycling does not seem to be hampering my injury. I was always conscious of my injury and what could potentially hold me up. And I said, “Well cycling does not seem to be an issue.” So I was thinking– I lived in Scotland at that time, I was thinking maybe the length of Scotland. And then my wife then found the world’s longest road which runs from the southern point of Argentina to Northern Alaska which is 22,000 kilometers. So she clearly wanted me out of the house.

John: [laughter].

Dean: Just so the listeners and viewers are aware, because of the curvature of the Earth, it is equivalent of cycling from London to Sydney and then another 4,000 miles. And I thought, perfect, that is the perfect challenge for me. So having only cycled 20 miles, I applied for the Guinness World of Records and Guinness came back six weeks later and said, “Yes, you have been successful on your application.” So I thought, “Perfect.” But during this period as well when I left the military, I have been doing a lot for charities and I was a Special Boat Service ambassador for Scotland, an ambassador for the Role of British Legion. I did a lot with regards to military charity. So for me, rather than just doing the challenge, I always like to give back in philanthropy or raise awareness. And so, I am going to massively name drop now.

John: Yes.

Dean: Good friend of mine, who is Prince Harry, him and I have known each other about thirteen years now. Him and I have done a lot of stuff with charity together before behind closed doors. So, I rang him up and I said, “Look, I am going to cycle the world’s longest road.” And he said, “What charities will you do it for?” This is back in 2016.

John: Right.

Dean: Himself, his brother, and Kate, they were just about to launch a campaign called Heads Together, which is about mental health. So I sat down with Harry, I was aware of mental health within the military. I have seen it first hand with some of my friends and obviously, experienced it myself. But I was not aware of how big of an issue it was throughout the whole of society. Be it postnatal depression, young children, teenagers, all the way to fully grown adults. It affects everyone.

John: Right.

Dean: So I thought that is the perfect campaign for this challenge. And that was the PAH team. So harry then introduced me to the Royal Foundation and we started the dialogue. The first meeting was how much are you planning to raise and I said one million pounds because I wanted to keep them at the table and I did not want them feeling, “Why are we here for ten thousand pounds?”

John: Right.

Dean: The enormity of the challenge have to replicate how much we are trying to raise.</>

John: Right, makes sense.

Dean: Yes, and then the second question that got posed was what is the message that you are trying to promote? I was like, I had not really thought about it because I was [inaudible] Harry asked me. So I sat down for a minute and I said, “well, physical activity helps your mental state”, and they are like, “oh no, you cannot use that”, I said “why not?” and they said, “because it has not been scientifically proven.” I said, “that is fine, but I do not need a scientist to tell me that I feel good when I am physically active.” So I ignored them anyway and carried on promoting that message and that was the message I was trying to promote in this challenge. So with mental health, its free coping mechanisms, one is medication which you are trying to avoid, communication is a big one, but for me, it is the physical activity, it is finding yourself.

John: Awesome.

Dean: So that was the start of the PAH project.

John: Okay good, and we are going to talk about how that turned out, because I know the ending because I have read your book now twice, but I want to go. So now, you started cycling, you had a goal…

Dean: Yes.

John: You knew what the mission was.

Dean: Yes.

John: It is 22,000 kilometers.

Dean: Yes.

John: You also had a financial goal, you put a million pounds on the line.

Dean: Yes.

John: What happens? Start the journey for us. How do you even figure out? I mean, obviously, you have always figured out who the right specialist are, but how do you figure out? Where you start, how you traverse this, the planning on this is just fascinating.

Dean: Going into this, I was not a cyclist, but coming from the Special Forces, coming from the private security, the success of those operations were down to that military stuff, meticulous planning, and detail. So straightaway, it is just pen and paper. What is the objective? This is the starting point, this is the objective, and I just took a military set of orders and just put it on the challenge. I just crossed out ammunition. The two elements of the challenge is the physical element, achieving the aim, and then there is the monetary element, trying to raise that money, and I think the monetary is even harder than the physical.

John: Right.

Dean: Again, Alana was the campaign director, she sort of manage, helped, assist, all the sponsorship as well. For me, I was doing the planning, I know fourteen countries and it is a lot more to it than just grabbing a banana and in cycling not, you know what I mean? There are so many things you need to consider, security issues, seasons, what time of the year you are going, you are going through a country in the middle of the elections. It could be–

John: Dangerous.

Dean: In unrest. There are so many factors you would not really think about, but these are normal sub-factors that I always consider when I am doing operations around the world. So, yes, I just put all that down to paper. But again, one of the things we did in the Special Forces, which I thought was great, it is called a hot debrief. As soon as we came off the ground or whatever we are doing, before we even go clean ourselves up, clean our weapons, anything else, you have a hot debrief. The three questions were what worked? What did not work? And if you are going to do it again, what would you do differently? We are always learning and always evolving. So I thought, no, I was reading magazines and books about the Pan-American Highway and learning about cycling, but for me, I thought the best people to ask are those who have done it before you.

John: Yes.

Dean: I approached the previous record holders, and I post those three questions to them. I gauged my plan on that. So, they all started in Alaska and finished in Argentina.

John: Wow.

Dean: All their issues were in Central and South America. Be it political unrest, bureaucracy at the borders, languages, spares for the bike, so for me, as a military man or a planner, I thought why take a gamble with the 2nd half of the challenge, why not address those issues early? Get them out the way, and then when you get to North America and Canada, you are in a good position.

John: Right.

Dean: One of the things I did is I actually did the opposite of everyone else, I turned on [inaudible], and I say, “well, that is my start point. My start point now is Argentina and not Alaska, which then changed the times of the years when I needed to cycle. So, that was the first part. As a soldier, I have been to the desert, I have been to the arctic, I have been to the jungle. Some of the areas I was going through, it went from plus 47 degrees centigrade to minus 18 on the chart.

John: Oh, oh.

Dean: You know, the Atacama Desert in Chile is 120 degrees Fahrenheit. I have done it in the desert, but I have not done it eight to ten hours on a bike. So when I was training, I thought, well how can I replicate those environments? So I flew out to Dubai, did a two-week heat training out there, so I could satisfy myself that–

John: You were ready.

Dean: Yes, I was ready. Central America is 100 percent humidity. I had a friend who had a CrossFit Gym out in Thailand so, I spent two weeks out there training, and altitude wise, there is a center down in London called The Altitude Center, the room is simulated to altitude. The biggest climb on the Tour de France is about 21 to 23 Kilometers, my biggest climb is 67 Kilometers from sea level to 4 and a half thousand meters in a day, so it is literally everything on steroids. So, I did a ten-hour static bike ride in The Altitude Center to again tick the box that I am comfortable in those environment, so that was sort of the things that were going on in the background in regards to my training. The money side, as you have mentioned, living in Scotland and I was having to fly down to London a lot to meet potential sponsors, to meet the charities as well, and you can imagine how difficult it is going into somebody’s blue chip companies, standing in front of the board and say, “Well, I have never cycled before, but I am going to cycle the world’s longest roads, break a world record and raise a million pounds for mental health. I think a lot them thought I had mental health problems myself, and showed me the door. But thankfully, this is 2017, and the Heads Together Campaign had now launched in UK, so it is very much a topic of conversation, and a lot of the corporates wanted to get behind it, like corporate social responsibilities as well.

John: Yes.

Dean: So, it is very much– I was going that way as corporates wanted to get involved it. Then, I clashed at the right time with a FTSE 100 wealth management company, and we had the conversation, I told them what I was doing and they sort of looked beyond me, they believed in everything I said. They even said, “we know you are not a cyclist, but we believe you are going to do it.” So, that helped a lot for me. At this point, I was using my own money, I have put fifty thousand pounds of my own money to get it up and running to where it should be.

John: Right.

Dean: These people have to believe that you are going to do it, and me putting my own money is a big thing. They thought, “well, if he has put his own money, and then, we believe he is going to do it.” So, that helps.

John: Dean, how much of a support group was on the journey with you? In terms of travel team and things of that sorts supporting you.

Dean: Yes, I sort of looked at it, I was not a cyclist. At the beginning stage Harry and I did a promo video together, and we are getting requests from all over the world of assistance. I needed like a bike mechanic, I needed a soft tissue therapist, I needed a medic, and things like that, so that I could just concentrate on the cycling. We have these guys come forward and assist us, but hindsight is a great thing. I thought people were doing it for the right reasons, and it was not the case.

John: What?

Dean: I always joke that the bike ride was the easiest part of the challenge. As you start evolving, the medic on day 13, I had to send home because he was bullying the documentary team, the mechanic, the soft tissue therapist in Mexico wanted to promote their businesses and sort of hijacked the campaign name. They said, “you cannot do it without us.” So, I left them in Mexico, and cycle with my friend who was driving the vehicle. Things you do not really factor in on paper.

John: Right.

Dean: Managing people’s ego.

John: Right.

Dean: Moving forward, everything has to be in contracts and NDAs and things like that. I just assumed that yes, they are doing it for the right reasons and they are professionals and in the end it was not the case.

John: So, let us talk about three goals here. A, the goal was to get through this whole Pan-American Highway.

Dean: Yes.

John: And then the million pounds, and then also, what was your timeline? Tee up, share with our audience your timeline that you are shooting for to beat that record?

Dean: Yes. When I applied for the world record, originally, it was 117 days.

John: Right.

Dean: When Guinness came back to me six weeks later and said you have been successful, it had already been beaten. No, sorry, it was 124 days, when I applied.

John: Right.

Dean: And it came back six weeks later, it has already been beaten, it was now 117 days. For me, when I was doing my planning, I was looking at potential scenarios and contingencies, but were certain things that were out of my control, be it natural disaster, [inaudible], third party influence. So, I thought, we use a thing called fudge in the military, we give ourselves a bit of fudge and so I said, I am going to aim for 110 days. Not because I wanted to smash it by a week, but should we encounter any of those situations, it is eaten into that fudge, it is not eaten into my record time. So, that was always my target, 110 days. I took 10 days off the South America world record and did it in 48 days. The original record is 58 days which is great. So my decision to go south to north was a great decision because I had a tail wind through Peru which is 2,500 kilometers, and logistically, it was not a good decision. You can get a vehicle from Alaska down to Argentina and not have a problem. Coming the other way, we had to swap vehicles in every country, which is slowing us up on the borders. So, Alana being the campaign director decided we will buy an RV and a four by four and get it shipped from Fort Lauderdale down to Panama so, when I fly over from Cartagena, those vehicles will take us all the way to the end. So, that was the plan. Alana got a phone call two weeks before I was coming into the end of South America saying that the vehicles had not been loaded on the container, and they are still stuck here in Florida. So, thankfully my wife, my PA, and a couple of my friends have foresight to fly over, and they moved the vehicles 4,000 miles in eight days, from Florida through Mexico, through all of Central America to Panama, and I broke the world record in the morning, flew over and an hour later, Alana came in with the keys. So, again, as we talked about earlier, Alana is very much running everything in background to keep the campaign going. What was great about that, not only so much the achievement that they did, but I have heard about bureaucracy at the borders, but I had not witnessed it in South America, that is because it was all to come in Central America. They got held up at gun point in some of the borders, and everything else. So, for me, it was great knowledge and information going in to the next phase. I would always cycle and make sure I hit the borders at night so, if we are held up it was eaten into my sleep time and not the cycle time. We got through Central America, I got to North America on day 17, I am like, perfect. I am now fourteen days ahead of my target. I was like, I could take a days rest if I need to. I did not realize how big an issue was getting into America. I did not know whether it was because of the language, that everyone now spoke my language, I did not know whether it was the calorie[?] options were a lot better. And also maybe because the previous record holders have never had any issues in North America and Canada, [inaudible], I have left everything behind me.

John: Right.

Dean: An hour after getting in, I had five missed calls of Alana. She is very good at keeping distractions away from me. My initial concern was my children.

John: Right.

Dean: I got into the phone, and she said, “Oh, we have been kindly invited to Harry and Meghan’s wedding.” How is that?

John: Great!

Dean: So, Alana being Alana, it only works out to me to get the last flight home was day 102, which is fifteen days ahead of the target. So going into the phone call, I was fourteen days ahead, ten minutes later, I am now a day behind. All my efforts have just been taken away from me. It is very nice to be invited to such a prestigious event.

John: Yes.

Dean: My time I was cursing. But then I got to Lubbock in Texas, and the next day it went 60 mile an hour winds and tornadoes, and I was grounded for another twenty-four hours. There is an app on your phone called Windy TV which gives you the strength and directions of the winds.

John: Right.

Dean: it did every hour for two weeks, and so I just put pens to paper. I just made a plan in that twenty-four hours, I had to cycle 340 miles in the next thirty-six hours to miss the next weather window, and I just played chess with mother nature through North America and into Canada. Originally, I had seventeen days planned for North America, cycle in eleven and a half. But the luxury I had being in North America and Canada was security.

John: Right.

Dean: In South America and Central America it was dictated by first light and last light, and I had to be off the road. Whereas, in North America and Canada, I could cycle through the evening, and that is where I got my gains and I got a week outside in a place called White Horse, and the world record is very much secure. The Royal wedding was secure unless I was going to get eaten by a grizzly bear. Then I got a phone call about a professional cyclist who was sponsored by all the big brands, Red Bull, the Austrian cycling team, who have just come out on social media that day, and said that he was going to cycle the Pan-American Highway in August and be the first man to do it under a hundred days. So that just changed the dynamics again completely for me. I cycled for twenty-two hours in the last thirty hours in minus eighteen to make sure that I came in and became the first man in history to do it under a hundred days. But the great thing about this, we talked about the importance of planning and everything else–

John: Right.

Dean: But it was actually, as we say in the military, the best plan in the world until they start shooting back. That was not in the plan, it is actually being reactive to the situation on the ground. For me, the situation kept changing. So rather than getting upset, I just reacted to what was in front of me, and if I had known about the wedding or the cyclist from day one, it maybe too much, you may have pushed yourself too hard.

John: Right.

Dean: But as it was in front of me, I was reacting even to the very last two days, the plan was changing.

John: Unbelievable! Share a little bit about how many miles did you average a day?

Dean: So, I finished it in ninety-none days, twelve hours, and fifty-six minutes. I had five days off, three due to weather, and two due to logistics. So, we have done ninety-four days cycling.

John: Right.

Dean: That would be an average of a 147 miles a day, for 94 days. But my average speed was 16.8 mile an hour. A lot of people asked me, such a huge talent, how do you break that down mentally? How do you compartmentalize that? And for me, it has been like a special forces selection is six months long. You do not go on day one thinking about six months.

John: Right.

Dean: You think about, what is in front of me today? What do I need to achieve today to get in position tomorrow. And that is why I did this, I broke it into countries, broke the countries into days, and broke the days into stages. So, nutrition and hydration were key for me to keep weight up. So, I would have breakfast, and I just cycle as fast as I could for two to two and a half hours, and I would get off the bike, have some food and water for 30 minutes. I was very disciplined in my timing. So, I was then back on the bike, and all I would do is look at the next two hours. I would not look at the afternoon, I would not look at tomorrow or next week. For me, it was just doing four training sessions a day.

John: Right.

Dean: Before you have done a day, you have done a country, you have done–

John: I want to go back to that word you just used, discipline, But before we do that, it is so fascinating in that you made it so it would not overwhelm you. It was two, two, and two, four times a day.

Dean: Yes.

John: Which does not feel overwhelming when you break it down like that, but if you wake and say, I got to go do eight hours, that is 16.8 miles per hour to get through today, that feels a little bit overwhelming.

Dean: Yes, it does. But I am very objective driven and I see other people doing challenges, and they are like–

John: Right.

Dean: Well, I am two parts behind today, what I would do is I will catch that up tomorrow. Well, you do not know what is going to happen tomorrow, you could have another back day and be 20 to 30 miles behind, which then plays through your head. So for me, I always make sure I hit my objective for the day, because then when you start the next day, whether you make those extra two or three phone calls, you know you are in a good place, you are where you should be the next day, which then helps you. So, for me I think I had really strong winds for the first week, and I was 39 miles behind by the end of the first week, but my target was still a week ahead in world record, and then once the wind has changed, I was then well ahead. I was then achieving my objective and getting further which then mentally, I was getting stronger and believe that I could do more. Before I had even gone over, I had never done more than 150 miles, and at the end, you average 147 miles for ninety-four days. So, it is just believing that you can do it.

John: We all love food, and I would love your little anecdotes in the book about the food quality in different places, and I especially love when you came in to Tim Horton’s and you talked about just your experience and your love of just running into Tim Horton’s and the donuts, and the coffee. How many calories, I know you have this measured, were burning a day? And you were having to consume a day to keep going.

Dean: You are averaging between nine and twelve thousand calories you are burning a day, but your body can only consume seven thousand from food, so the rest have to come through fluids. So, I knew from the start it was almost like an arctic exploration, I would lose weight from the day I started to the day I finished. I think in America with Tim Horton’s, thanks to them, I actually put a bit of weight on. But I do not look like a cyclist, I am very stocky. When I started the bike ride I was 90 kilos. I remember my coach, he had his way, he had me as thin[?] as his pen on day 1 at two to three percent body fat, but again, going into the ride, I had knowledge with my time in the military like, our special forces’ selection is six months long. You start one hundred percent fit and in pristine condition, you will burn out week two or three, now this is not a sprint, this is a marathon.

John: Right.

Dean: So, I always start at seventy-five to eighty percent fitness, but carrying weight because then what you do is you shed the weight as you get fitter. The first few days are always hard, I mean, you start eating in to your reserves. So, I finished to bike ride at 78 kilos. I lost 12 kilos in weight. The decision to keep that weight on early was a good decision.

John: Before we get going, we have Dean Stott with us, you could find Dean at deanstott.com. Also, his great book, I have read it twice, I bought two cases for my friends, family, and company. This is a great and inspirational book here, and I recommend everybody reading this book. Buy it on amazon.com, Audible or anywhere where great books are sold. Look at how many places I marked it up on. I mean, I just really enjoy the book. Let us go back. Now, you finish up, you have made it to the wedding, thank God, you have made it to the wedding, talk about the financial goal, how did that work out?

Dean: So, when I crossed the finishing line, we raced, at that point, it was over five hundred and thirty thousand pounds.

John: Wow!

Dean: No, about six hundred thousand. Before I had even set off, the company who had sponsored me had an annual company meeting in London, and they said would I come down and guest speak at the O2 Arena in front of ten thousand people, I said, “Yes, of course.” That evening, they raised two hundred sixty five thousand pounds and doubled it. So, before I had even gone on the rides we had five hundred and thirty thousand. We then raised another thirty thousand through the general public. My PR team, thirty thousand pounds is still a great achievement, but they said, “You are showing no emotion.” People like to see people suffering, when you come on it was almost like a military operation, and that was me, I think once I break down in tears, you know, I crashed a bike in Chile and had food poisoning in Peru, maybe I should have called it a day, but I was trying to promote that unrelenting pursuit of excellence. But after coming back, we also had the main fund raiser, big event in The Hilton, in London and Harry came along as a guest on the stage and did a Q&A session, and there we made another three hundred thousand pounds as well. But what was interesting is the fact that, before I had even gone on the bike rides, we had raised seventy thousand pounds in an event in Scotland, and fifty thousand pounds of that was a deposit for the hotel in London, so before I had even gone on the bike ride, we were planning the welcome back party, and then the events manager, she kept saying to me, she said, “but what is your contingency?” And I never used to answer it. Alana would answer, she said, “Well, a contingency is we go to Dean’s funeral.”

John: Oh my gosh!

Dean: When I got back actually, I sat down with her and I said, “I never used to answer because for me, there was no contingency. If I knew there was an easy option or there was an alternative. When things get hard, you are naturally stirred to that alternative options. So, I just blocked out all my outs, there was no other outcome other than actually doing it. I told her that and I think she then got my sort of mindset.

John: Dean, now, I am sensing something now, you are sitting today in Southern California. You have moved now over to Southern California. So, you are available for speaking events in the United States, and also to promote this great book that you have now in the United States, Relentless – the relentless pursuit of excellence. I am sensing a little bit of a kumbaya here. Wait a second, Harry has moved to Southern California, you have moved to Southern California, are all of you guys now moving to Southern California and hanging out together? What is going on? I want to understand, what is this–

Dean: Alana and I, when we met eleven years ago, I was down in San Diego with the Seals down there doing some work, and she had just done a road trip as well, and we just love America. We love the vibe, the lifestyle, and it is trying to– and so for us, we were getting really busy again, and we sat down in Christmas and said, what is it that is important to us, and it is that balance of the Ying and Yang, with the lifestyle, with the family. California has always been the place that I had fancy, and [inaudible] there is no good time to move. But moving during the pandemic, wild fires, and on the eve of election, there is better times to move, but for us, I always joke that I have stepped off helicopters into worst.

John: We are very grateful to have you here, and you are going to be a huge success in the US. You know, two questions I have before I let you go today. A, you look, still, amazing physically fit. What do you do everyday now to stay in shape, ready to go shape?

Dean: Yes, as I have touched on earlier, physical activity helps your mental state.

John: Yes, agreed.

Dean: Now, when I get grumpy, get on your bike, go do some CrossFit, do something. So, for me, my USP, which sets me aside from other adventures is I take a challenge or a discipline I swore I have never done before and find the biggest challenge. So, my next challenge which is penciled for this year, which is obviously now moved because of COVID, is to kayak the river Nile from source to sea [?] which has never been done before. The most I am trying to promote people is, it is never too late to start small. I am forty-three, I broke my first world record at forty-one. I am really trying to get that message across. So, I do a little bit, I mean, I still stay on the bike. I still do some upper body stuff. I do not do weights, I have never done weights. This whole body weights stuff.

John: Really?

Dean: Yes, because in the military, we used to get tested in the military but it was never, how much can you bench press? It was almost how many pull ups can you do? How many bends or press ups, so I always focus my energies on that.

John: Level of intensity, of difficulty. Rate, I want to do a compare and contrast now, the Pan-American Highway Challenge that you did, which obviously, you have accomplished and beat the world record, and now have set the world record, and kayaking the Nile. Compare and Contrast.

Dean: Two very different challenges, the Pan-American Highway, there was a world record, there was an objective to hit. I had a target to hit.

John: Right.

Dean: The Nile, no one has ever done it, you are setting the bench mark there. So, for me, I am very conscious that I have set my own goals in my head because I do not want to be out there nine months later, paddling. I have got a family. But there is more of a story to tell. I would not be tapping my watch to the documentary team every five minutes. If there is something of importance to record then we will do it. But I have a number in my head, it is a hundred days again. I going to go for a hundred.

John: Now, I am not by any means a Nile river expert, but I have read that there are crocodiles in the Nile river.

Dean: Yes.

John: This is not just a physical and mental challenge to bet your upper body and your cardio in shape, respiratory in shape too, pull this off, you might be navigating very dangerous waters at different times during this period. Is this not true?

Dean: Yes, very true. It is the world’s longest river. It is 4,280 miles. It start from Luanda and you got crocodiles, you got hippos, you got civil war in South Sudan, you got malaria, it has got everything. Which again, is a great challenge and a great story. What I love about it is, the Pan-American Highway the roads are there and it is more physical, but this there are going to be different tribes, different culture, and you actually do not know how to move along the Nile unless they say so. So, having those local fixers, it is going to be great. I always promote the physical activity mental state but with the Nile, it is great. There are so many arms from it, raising awareness slavery and human trafficking, poverty, pollution. The Nile is the lifeline of Africa and it has got the most powerful waterfall in the world as well.

John: Will there be a fund raising element around that as well, Dean?

Dean: There will be. I will have a fund raising but I would not be so fixated on that because that would very much distract you from the goal.

John: Fair enough, fair enough. Dean, I look forward to meeting you in person. We welcome you to America. We are grateful for your service, fighting for freedom around the world. Do you have any last things you want to promote before– I am going to promote your book at the end here. Is there anything else you would like to say before we sign off. I am so grateful for all the time you spent with us today.

Dean: I appreciate your time and one of the other reasons I am over here is, one of the feedback from the book is yes, you are a great endurance athlete but you are a security expert, why are you now in that. So that is also one of the reasons I am here is to promote another way of skinning the cat when it comes to security. Just purely from my experiences around the world, and they have obviously been successful. I just love to help people. I can do that.

John: For our listeners out there, Relentless, Dean Stott’s Relentless, you can get it on Amazon, you can also buy it on Audible, or on his website www.deanstott.com. The unrelenting pursuit of excellence. You want to inspire others, you give them this book, you tell them read this book. They will pursue excellence after that. Nothing is impossible if you read this book. Dean Stott, I just got to tell you something, thirty-two years ago, I moved to California with my family, young family, and my daughter and I used to spend a lot of time– we did not know anybody, we are in Redondo Beach, and we used to go to a little shop down the street, it was called Good Stuff. It was the first time, she was a little two-year-old, she saw a man in a wheelchair, and she used to go up to that guy and he befriended her and she befriended him, and she became very comfortable around him, he was just a lovely human being. This became a ritual every week and after we had lived here for a year, it was in 1989, I picked up the newspaper one day, I saw he was on the cover of the July 4th weekend newspaper entertainment section. I said, why is this guy that we see at the little shop every day on the cover of the entertainment section? And he was a gentleman named Ron Kovic. A movie on his life called Born on the Fourth of July had just come out with Tom Cruise playing his life. I read his story that day and I watched the movie, and I always say to myself, if I ever have the opportunity to honor the veterans that fight for freedom, fearlessly fight for freedom, I am going to make use of that platform and I got lucky in life with business and I got very lucky and honored with this podcast. Dean Stott, I am honored and blessed to say that you came on today, graciously came on today, and I am grateful for you as a human being on what you have accomplished, fighting for your great country, for freedom and democracy around the world, and what you did post-military is also unbelievably inspiring. You are a great human being. I am grateful for you. Any way I could introduce you to anybody in this great country, you deserve as much publicity.

Dean: Amazing. Thank you so much. I really appreciate having me. It is an honor especially the first one, the first veteran.

John: You set a very, very high bar. There is going to be much more to come. We are going to have you back again. Before you go to the Nile, we are going to have you back so you could tell the story of the Nile. I am sure that is going to be a whole another book. Thank you again for everything. I cannot wait to receive our books from you. We are going to share with our company, I am going to share with lots of friends and relatives. Continued success and thank you for all that you do, Dean Stott. Thank you again.

Dean: Thank you very much, John. I appreciate it. Thank you.