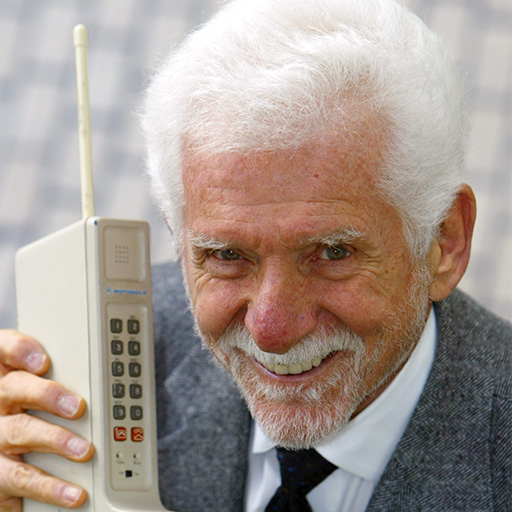

Martin Cooper is an engineer, an entrepreneur, and a futurist. Known as the “father of the cell phone,” he invented the world’s first portable cell phone while at Motorola and made the first public cell phone call in 1973. Over thirty years at Motorola, Cooper and his teams introduced the first nationwide mobile phones and radio pagers, and numerous other products. He and his wife, Arlene Harris, an accomplished inventor and entrepreneur, founded over a half dozen companies.

John: Do you have a suggestion for a Rockstar Impact Podcast guest? Go to impactpodcast.com and just click “Be a Guest” to recommend someone today. This edition of the Impact Podcast is brought to you by ERI. ERI has a mission to protect people, the planet, and your privacy, and is the largest fully integrated IT and electronics asset disposition provider and cybersecurity-focused hardware destruction company in the United States, and maybe even the world. For more information on how ERI can help your business properly dispose of outdated electronic hardware devices, please visit eridirect.com. This episode of the Impact Podcast is brought to you by Closed Loop Partners. Closed Loop Partners is a leading circular economy investor in the United States, with an extensive network of Fortune 500 corporate investors, family offices, institutional investors, industry experts, and impact partners. Closed Loop’s platform spans the arc of capital from venture capital to private equity, bridging gaps and fostering synergies to scale the circular economy. To find Closed Loop Partners, please go to www.closedlooppartners.com.

John: Welcome to another edition of the Impact Podcast. This, my friends, is going to be a very, very special edition because we have with us today Martin Cooper. He’s the chairman of Dyna LLC, but much more important than that for this conversation, he’s called the father of the cell phone. Welcome, Martin, to the Impact Podcast.

Martin: Great to be here, John.

John: Martin, before we get talking about how you created the cell phone, what things were like back then, and how you think they’ve evolved since then in terms of the cell phone and technology, I would love you to share a little bit about yourself. Where were you born, and where did you grow up and get on this fascinating journey that you’ve been on?

Martin: Well, you have to go way back in my memory to talk about those things, but I was born in Chicago 96 years ago, getting close to 97 now. A very, very different world than we have today, but I still have memories of those times. My folks were emigrants. They emigrated from Russia around 1920, a little earlier than that, to Canada, Winnipeg. Winnipeg is a place in Canada that most people say they are from because nobody stays there very long. They don’t have to. It’s very cold in Winnipeg. But they got married in Winnipeg. They moved to Chicago, tried to start a business, and that’s where I was born. [inaudible] we’re not going to discuss now. They ended up going back to Canada, tried some other businesses. They stayed in Canada for 8 years or so, went back to Chicago, and finally got into the business that we’re both successful at. That’s the history. One aspect of that is that they both worked very hard, and we got with it. I spent a lot of time alone. [inaudible] That’s how I became a dreamer. That has been the one focus of my life. I do a few practical things now and then. I’m a free-range thinker. It’s very hard for me to be focused on one thing, but I’ll try to focus on you for the next hour.

John: When you were growing up as a child, were you excited about school and reading and learning, or were you more of a creative dreamer even from your childhood?

Martin: Oh, no. I was an avid reader. I can still remember one of the first books. I still remember being at the library in Fort William, Ontario, which is a part of Thunder Bay now. I remember it because I was very short, and I was looking at the librarian up in the hall, and she says, “Are you sure you want to read that book? You’re just such a little boy.” I said, “Yes, I want to read it.” It was ‘Moby-Dick.’

John: Oh, wow. Herman Melville.

Martin: That’s exactly right. It’s a very deep book, as you know. I’m not sure what I ever thought at that time, but I’ve read it over twice since then. But I was an avid reader because you could do reading all by yourself, no matter where you are. That has been a focus of my life.

John: Then you graduated high school, and then you went to what? The Illinois Institute of Technology?

Martin: That’s right. I got interested, for whatever reason, in technology from the time I was a little kid. I wanted to know how things work. I have a recollection of watching some boys with a magnifying glass burning paper. You ever do that, John?

John: Yeah, as a kid that was a big deal with the sun.

Martin: Those little things were so important to me. I took a Coke bottle and broke the bottom off, tried to make a lens out of it. That didn’t work. That’s how I learned about experimenting and accepting failure. By the time I got to high school, I knew I was going to be an engineer of some kind. I went to a technical high school. What I didn’t know is that technical high school is another word for trade school. It was the smartest decision I ever made because the teachers at this school did very well at the non-technical courses. I took a shop every semester of my time at Craig Technical High School. Everything from print shop, wood shop, [inaudible] forge, boundary. If you think about it, all these are tools. As an engineer, everything is changed, but the principles are the same. You use a tool in ways that you don’t chop your fingers off. That rule is still the same, isn’t it, 90 years ago? In those days, when kids go to college, by definition, they go somewhere away from home. In those days, we couldn’t afford that. I went to the best technical college in the area, Illinois Tech. It’s still an extraordinary university. I’m now on the board of directors of the Illinois Institute of Technology. They’re as extraordinary now as they were then. Those were very lucky decisions in my life, John.

John: You graduate from the Illinois Institute of Technology, so you made some great decisions. You got educated. How was the job market then for someone like you, who was an engineer/dreamer, visionary? What were you looking to do out of school?

Martin: First of all, I have to say that I could not afford to go to the university, even though I still remember how much it cost to go to Illinois Tech. The first year, it was $162 a semester. It’s tens of thousands now. The way that I got through school is I joined the Navy in the ROTC. The Navy paid for my education, but I was obligated to serve with the Navy and become an officer for 3 years. I was very courted[?] to doing that. I loved being in the service. I became a submarine officer. I really had a tough decision to make about whether to stay in the service, but I was very fond of the young women in Chicago, and so I made a decision. I was going to leave the service, tell the Navy that I was leaving, and then two weeks later, I got a message from my girlfriend, who is no longer my girlfriend. She decided [inaudible], but I left the Navy. In any event, the place that I would die to go to was the laboratories. I didn’t have a doctor’s degree or a master’s degree at that time, so that wasn’t in the cards. I tried to go to the Armour Research Foundation. Once again, I was not educated enough. Even though being in the Navy was an education itself, John, they really helped me grow up and learn how to deal with people, how to get people to do your bidding without antagonizing them, how to face problems without getting panicked. That was a really important part of my life. I got a job as an engineer. My first job was a total failure, and it turned out to be one of the most important failures of my life. I went to work for a company called Teletype Corporation. You’re too young to know what a teletype machine is.

John: No, but Martin, explain what you mean your first job was a total failure. What does that mean? Explain what that means to you, because that’s a very important lesson for our young listeners out there to hear that failing is not really a bad thing. It’s part of the journey. I want you to explain why you thought it was a good failure.

Martin: Let me tell you, you learn more from failures than you do from successes, because you know as well as I do that at least one of your successes is this podcast. I’m sure you have some problems and false starts. When you’re successful, you can be successful because you’re lucky. When you’re a failure, you know you did something wrong, and you learn from every failure. The wrong thing I did was sign up for a company whose product was destined for failure. The teletype machine was an all-mechanical machine for communications. As you know, there is no such thing as a mechanical communication device anymore. So that was the bad part about it. The good part is that the teletype company was part of the Bell System. They operated with the same principles as the Bell System, which was a monopoly. I can tell you very briefly the difference in the labor[?] of the company. They hired me as a research engineer. I sat in a room with 100 other engineers doing various other things. We worked during the day. At lunchtime, at break time, at the time the bell rang, everybody stood up and walked out. I lasted a year there and got a job at this small company in Chicago called Motorola. I was in a small group of engineers. We worked in an old building. We had to be careful because on hot days, tar would drop from the roof. Somehow, I got time to go home every night. If we were engaged in the conversation, we just kept going. The job was interesting, challenging. There was so much difference there. That’s where I learned what the difference is between a monopoly and a competitive business because I’ve spent most of my life fighting with the Bell System and with other monopoly kinds of systems. I knew how they think, how monopolies think. I know how much more effective competitive systems are. Sorry about the lecture there.

John: [inaudible] Teletype for 1 year. I was at Motorola for 29 years. But I should tell you that during that 29 years, I worked at at least seven or eight different jobs. Each one escalated in one way or another, taking more chances and having my share of failures and other successes. Motorola was wonderful in that regard. They recognized that people who take chances do fail on occasion, and they recognize good thinking and successes. I ended up being at Motorola for 29 years. The only reason I left is I had gone about as far as you can go in a company like this. I’m still the [inaudible] as a [inaudible]. You’ll forgive me. That’s when I left Motorola and started a new business.

John: So while at Motorola, you created, invented, and I want you to walk me through this, made the first public cell phone call in 1973. Talk about how did this whole journey go. How did you envision this? How did you make it happen? How many people were on your team that you were leading, and how did that all work out?

Martin: Well, the first principle that I learned at Motorola is that whenever you talk about technology, the first thing to think about is the people, not machines, not theory, but what problem are you solving? What human experience are you affecting? That started very early. The first devices that I got involved in had to do with mobile telephones, car phones. One of the elements of car phones, the way that they discriminate; they make a phone ring to the car, so the mechanical device went “click, click, click, click, click.” At that time, I always hate to talk about stuff about how old I am, John, the transistor had just been invented. The guys at Motorola were experimenting, and they had learned how to make some very early transistors. They sent us some samples, and I decided I was going to figure out a way to make the transistors perform the stuff that these mechanical things were doing. The transistors arrived from our semiconductor division in a wooden keg. Like you get a keg full of cider, then the keg full of transistors with the leads all on and [inaudible] wound together. Other engineers had tested these and taken all the best ones, and some [inaudible] learn to use these transistors later on, maybe 3 or 4 years later, that became a product of Motorola. We delivered in all these categories, and I got involved in a bunch of other small products, each time building up a little confidence, but we did get a chance with that.

John: How long was the process from you envisioning this new invention to actually creating it and then making that first personal cell phone call?

Martin: That’s right. I was the first person to actually move from engineering to what they call product management, and that product was pagers. You know what a pager is [inaudible]?

John: Yeah, from my childhood.

Martin: I can’t tell whether you dye your hair.

John: I’m 63 years old.

Martin: When I was 63, my hair was white, John. I showed you the difference between working for a living and having fun like you’re doing. I actually became a product manager of paging, where I was involved, not only in engineering but marketing as well. That’s when I encountered the Bell System because the Bell System decided that they were going to go into the paging business. Motorola was dominant in that business, and the Bell System thought that they could do it better. We did sign up with them to help them get into the business. They’d go to the paging terminal. You have a metro station in the middle of the city, and you send signals out, and you beep the people you want to reach. For those of your listeners who have no idea what a pager is, there are still pagers in existence now. At that time, a company would have just enough pagers that they could reach their own people, and the Bell System said, “We want to do citywide paging.” I thought about it for a while, and I said, “Why citywide? Let’s do it all over the whole country.” The Bell System’s design was to have a terminal, a central station, that could reach 3,000 people. I put a team together, and our product reached 100,000 people. Finally, the Bell System gave up. We became a dominant provider while I was in that business.

That’s where I learned about the Bell Laboratories being a monopoly, why monopolies do not take chances. They don’t really think about the customer; they think about the technology.

John: What year were you working on that first pager, from city to national? When were you working on that? What was the time period?

Martin: Around 1969. [inaudible] ’69. Coincidentally, that was the time when the Bell System announced that they were going to come out with a national car telephone system. That’s when I decided that we had already done car telephones. We had already done them mostly transistorized. We were dominant on that. I decided that the Bell System was all messed up. I was in the paging business, portables. My first public statement of that was the following. People are mobile, yet for 100 years, the phone company, the Bell System, told us that the only way to communicate with somebody else was with a wire between the two people. They were wrong. So there you go, the idea of people first. In 1969, we started a 12-year battle with the Bell System. The Bell System had decided that the portables were not technically possible at that time and that the way to go was with car phones. I had already done car phones. I was ready for the next generation. Motorola took the Bell System out. In 1973, there we are.

John: So, 1973, talk a little bit about the first public cell phone.

Martin: We had been really working hard. I testified before Congress, testified before the FCC twice. We were making some headway. I had a relationship with the chief engineer of the FCC, but the Bell System was the biggest company in the world: most people, the most revenues, most profits, and a monopoly on top of that. They were a really tough competitor. They were starting to make headway. In Washington, we had three people covering the Congress and the FCC. The Bell System had 200. They would call the chairman of the FCC every week, and every commissioner every week, and every congressman every week. We were really getting desperate. The issue with Motorola was with the Bell System was supposedly not only to do cell phones, car phones; they were going to take over the two-way radio business, which was Motorola’s most profitable business. Motorola was interested in keeping them out of the two-way radio business. That’s when I decided, why can’t we build a better device than what the Bell System was supposed to do? My management supported me. Anything that would beat down the Bell System had to be good. They were going to do a demonstration in Washington to explain to the senators and the congressmen how important two-way radios are. I have to tell you, John, there’s nothing more boring than what two-way radios do. They are the glue that keeps all our industries running, all those UPS trucks around, all the police, fire departments. [inaudible] are services that don’t affect consumers. I said, “If we’re going to get the attention of the congressmen and the FCC, why don’t we talk about something that appeals to them, and that is making these two-way radios, the car telephones, personal, because I think both are going to take over. The management supported me, and we were about ready to do a big demonstration of two-way radios in Washington. I said, “I think we could build a handheld portable telephone.” That’s when we came up with the very first phone, and you know what the history of that is. I went to the management in November of 1972. By December, they had given the approval. I put a team together in March of 1973, and we had a working unit in the laboratory. And on April 3rd, 1973, in front of the Hilton Hotel in Washington, D.C., we demonstrated a working handheld portable phone.

John: You talk about putting people first in your last communication. What was your first communication on the cell phone?

Martin: Well, there was an amusing idea. There was only one thing I was thinking of when we were standing on the street. Remember, this was before the integrated circuit was widely used. The parts were all wired, hand-wired together [inaudible] a laboratory. And the only thing [inaudible] works. I’m talking to a reporter, not unlike you. I’m just standing on the street. And at the last minute, I got to the point of enjoying how it worked, and I hadn’t thought about who I was going to call. And the mic flashed away. I pulled the phone book out of my pocket, gives you an idea of what the state of the art was [inaudible]. I looked up Joel Engel’s number. Joel Engel was my counterpart in the Bell System. He was running the mobile phone system for the Bell System. Bell Laboratories was doing the actual work. I called up Joel’s number. So I called Joel’s number, and remarkably, he answered my phone, not the secretary. I said, “Joel, this is Marty Cooper.” [inaudible] thrilled. They considered Motorola and me an annoyance, getting in the way of their plan. And since they were monopoly, when they made a plan, they did it. But he said, “Hello,” I said, “Joel, I’m calling you on a portable telephone. I’m calling on a handheld telephone.” And he says, “Really?” I said, “Yes. This phone,” I described it to him. It weighed two pounds. It had a talk time of 20 minutes before the battery[?] ran out. To this day, Joel did not admit that I ever made that call in the first place, and I don’t blame him. 12 years later, the Bell System was still not accepting that. They were still trying to get the world to have car telephones. The first Bell System demonstration of what we call cell phones today was in Chicago, of all things, and it was all car telephone. Our first demonstration was in Washington in December of 1973, all handheld phones.

John: Did any of the reporters that were there record your first call? Did they have a recorder next to you while you made that first call?

Martin: No, they didn’t. I was all alone on the streets of New York, but in the afternoon, we did hold a press conference. There were not many people there, but it did get the attention of the press, and that telephone was conscribed in every country in the world. So we changed our objective. We got people’s attention.

John: That’s amazing. So you made the first call. It was successful. Besides the thought of “I hope this works,” after you made that call, when you were reflecting in the next 24 hours with your wife on what just happened, what did you think was going to be the outcome, short-term and long-term, from this new invention that you created?

Martin: Well, the first thing is we had to convince the world that this handheld telephone was going to be a big deal, because the Bell System was saying there will not be very many people using these handheld phones, and that being the case, there’s no business there. We were willing to stick our necks out, but we weren’t a monopoly. They wanted to be the only provider. Well, that started what I described to you as a 12-year battle, of Motorola trying to dissuade the world, and mostly the FCC, because they were the decision makers, that it would take long to do that. The way to do it was to have a competitive business, and the market should decide whether they are portable or car telephone. Thousands of pages of filings with the FCC. As I told you before, I had to testify twice with the FCC. I would love to tell you, mostly it’s self-aggrandizing, but that’s what we’re doing here. I was in the conference at a committee meeting. Senator Inouye of Hawaii was the chairman of the Ways and Means Committee. It was a very important committee, and he was one of the top active senators. The first session in the afternoon, they had four speakers from the government talking about the need for radio spectrum. Then they had a break, and the next people were from industry talking about the radio spectrum. And me being naive, the first time I’d ever been in a role like that, talking to a bunch of congressmen, this thing was set up like a trial. I was chatting with somebody, and I go to where the speakers are. There were four speakers. They had four chairs in front of the table. It turns out there were five speakers, and the four chairs were already occupied. There was no room for me. So they immediately ran off and found another chair. Here are these four speakers sitting at a table, and I’m sitting off to the side. They called out the speakers, and each one of them spoke. My turn came up, and they introduced me. I said, “Thank you very much for the opportunity to be here speaking to you today, and thank you for the opportunity of being last so I could explain to you what everybody else meant to say.” You can’t appreciate that unless you know what they were doing. He was a really serious guy. He looked like a totem pole, no expression. When I made that comment, first of all, everybody in the room laughed because there was relief after all these serious discussions, and then he actually smiled at me for the first time [inaudible]. So the bottom line is that we ran some competitive tests in 1981, and at that point, the chairman of our company, Bob Galvin, who was the son of the founder of the company, was calling on his friend, George H. W. Bush, and he demonstrated one of the children of the ones that I demonstrated. It looked identical, except it was now a little smaller, a little more reliable. Reagan called his wife, Nancy, which is what everybody does when they get their new phone. In those days, you called your wife or your best friend with this new gadget that you have. Bush was really impressed. He said, “Well, hold on.” He walked into Reagan’s office, and of course, Reagan called Nancy. You guys might hear that call. A very successful call. Reagan says to Bush, “Why don’t we have them?” This came secondhand. Bush said, “Well, the FCC has been dragging their feet for a number of years,” and Reagan said to Bush, “Make it happen.” Within weeks, they announced that this new system was going to be public as soon as they could figure out who the first providers were, that the system would be competitive, not a single company, and that the nature of the system would be determined by the market. It would not be either a car telephone system or a handheld phone system, which is what the market required, fortunately. In order to allow handhelds to be used, you had to design the system the way I had designed it. Otherwise, it wouldn’t work. If you think about it, [inaudible] telephones are two-dimensional. Handheld phones go up in an elevator, and that introduces a whole bunch of new problems, which we have solved [inaudible]. So I don’t have to talk about the result. 80% of the people in the world today have telephones, and in part, handheld phones. I’m getting carried away with my own story. 80% of the people in the world today have phones, [inaudible] handheld phones,. [inaudible] more handheld phones, in a different way, than there are people.

John: Well, let’s just say this: in 2025, the cell phone, which I’m holding up here, is the most used device in the world. Did you ever dream back in 1973 or 1981 that this was going to revolutionize how we communicated the way it did?

Martin: Absolutely. We were the voice in the wilderness. Nobody believed us, but we predicted that someday, when you made a phone call, the only way that you would be out of the air is with a handheld phone. We’re all out there today. As I said before, 80% of the people in the world have a huge [inaudible], but it’s an integral part of their lives. They have changed their way of doing things.

John: Well, you democratized communication, Martin. That’s what you really did. You democratized communication.

Martin: Having said that, John, I’d like to give credit for [inaudible], but there were dozens of people who worked on that project with me to get this thing started. There were thousands of people who created this industry that we have today, but I would say that my persistence and the vision may have had something to do with it.

John: Martin, talk a little bit about this. You’re a family man. You’re a husband of many years. You’re married to Arlene Harrison. You have children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren.

Talk a little bit about some of the great outcomes that have come from the cell phone in terms of democratization of information and learning and teaching ability, but also some of the negative outcomes that none of us ever thought were going to happen. How do you balance the positive with the negative now that we’re sitting decades away from 1973 and ’81? Where do we sit today with the beauty and the elegance of the cell phone and what you created, both the positives and negatives? Because you’ve got a worldview in that you’re not just an inventor and a visionary and an entrepreneur. You’re also a family man.

Martin: Well, there are downsides to the cell phone. I don’t have to talk about the upsides. The biggest one is productivity. Would you agree with that? [inaudible].

John: Yes.

Martin: There are so many things in life that you do more effectively because of the cell phone. The second one is safety. [inaudible] six-year-olds have cell phones today because when their mother picks them up at school, they may be standing on the street waiting for them. Just that safety factor alone. So you don’t have to prove what the effect of it is. [inaudible] cell phones are misused. That’s true of every technological advancement, but you have to look at the issues one by one. The one that I really love to talk about is that at least six or seven governors are proposing or have succeeded in making the cell phone prohibited in schools. That I would suggest, John, is one of the most stupid things that I’ve ever heard anybody think of or do. Think about it. All the rest of us, all the adults from college on, are going to depend upon the cell phone, the technology, the ability to reach anybody in the world, access to all the information in the world, but we’re not going to let the kids have that capability in school. The cell phone ought to be one of the most valuable tools in school. The problem is, and it’s a very real problem, John, that you cannot teach the same way that you taught before. You can’t give an exam and let kids have a cell phone where the exam and all the answers are all available. You have to change the educational system. So I don’t disagree with the governors in the sense that the system has to be changed to accommodate the cell phone. They ought to have specialized cell phones for kids. Cell phones should be a tool of education, not something that’s prohibited. In fact, I’m not crazy about the progress that’s been made in the way cell phones are manufactured and designed today, because even though there’s not a monopoly, there are just a few companies that are building cell phones today, and they are competing with the same basic products. So that’s just one example. The form factor of phones is simply wrong. The biggest opportunities of the future are, first of all, in education, second of all, in healthcare. If you think about the biggest thing that’s going on in healthcare today, it’s the ability to examine a person, measure what is going on in their body, not with a once-a-year physical evaluation, which is essentially worthless, because by the time you get measured, your disease has been there for possibly a year. You’ll want to be measuring people continuously and anticipate when somebody is going to get sick and nip it in the bud, stop it. The only way to do that is to first of all have a cell phone actually intruding on your body and measuring various parts of your body, based upon your history, based upon your genetics, based upon your health history. When a problem happens, the system, through the cell phone, hooks up with a hospital or medical system, and you’re either advised to go to a hospital. They tell you what to do. The potential is that we can eliminate disease. You can’t eliminate people getting killed, because one of the negatives of cell phones, how many times you’ve seen people walking across the street or driving a car talking on a cell phone. The one thing that technology cannot eliminate is stupidity. We do have some problems, especially now with the technology of reproducing people’s voices. It’s possible to have somebody call you on the phone.

John: You’re right.

Martin: And pretend there’s somebody else, but you could do that with a landline phone as well.

John: It’s funny, Martin, you brought up education. I can’t agree with you more. I think you’re spot on. I find myself, I’m 63 now, and I have a love-hate relationship with my cell phone. What I love is that I constantly find, eventually, there’s new tools that you fall in love with again. I remember when Spotify came out, and I’m able to listen to all my favorite podcasts on the cell phone. And now with AI, I’m able to go and query a lot of new AI LLMs, and there’s so much new information available to all of us. It’s like a new education that’s now available vis-a-vis our cell phones. So the cell phone continues to keep delivering wonderful ways of democratization of information. I think you’re spot on that education is really such a wonderful tool that our cell phones keep delivering to us.

Martin: That’s right. You could go on and on about this. I believe that because of the cell phone, education keeps going at a much faster rate than it would otherwise. People are living longer now. I’m not attributing all of that to the cell phone, but what living longer means, that the old paradigm of, let’s say, you’re born, you go to school, you graduate from college, you get married, you get a job, you retire, and you die, well, it turns out that people now have two, three, or four careers. So they’re learning continuously in their lives. The cell phone is one of the most valuable tools of education in that process. So I have to beat it to death.

John: Look at you. You and your wife are just perfect examples of what you just said. You’re a serial entrepreneur. You are an entrepreneur. Really, you were an entrepreneur in residence when you invented the cell phone and made the first cell phone call. You’re an entrepreneur in residence, but an entrepreneur in reality. Then you went on to form Dyna with your wife and keep inventing. You’re a serial entrepreneur, Martin. What other great inventions have you and your wife accomplished after the cell phone? What did you go on to do with Dyna, just to show you keep reinventing yourself decade after decade? You’re still not only a legendary entrepreneur and visionary, but you’re still a creator. Talk a little bit about that journey after 1973 and 1981.

Martin: Well, I should mention Arlene, because Arlene is more smarter than I am. She is held back by the fact that she’s a woman, but she’s working very hard to fix that problem.

John: How many years have you been married, Martin?

Martin: We don’t really [inaudible] when we got married because we’ve been [inaudible] working together for 45 years.

John: 45 years. Wonderful.

Martin: Arlene invented the Jitterbug phone because she took exception with how hard it was to use smartphones and how much trouble older people and people who didn’t like technology [inaudible]. Her first contribution was the Jitterbug phone, which is still being sold in various forms, and it was very successful.

John: And that was in partnership with Samsung, the great Korean brand?

Martin: That’s exactly right. I introduced her to people at Samsung, and I had the privilege of watching her sit with the president of Samsung. He personally contributed to the design of the Jitterbug phone. That’s how excited he was. If Motorola or any big company came in and told Samsung you want them to design a phone, they would not have considered it. They sat there building Arlene’s phone for her.

John: So really, you’re the father of the cell phone, but she can also be called the first lady of the cell phone.

Martin: That is what we call it. She deserves that in every sense of the word. She’s still very active in the industry in so many ways that it’s hard to describe.

John: So you’re both entrepreneurs and visionaries. What’s the great quality that you see across other entrepreneurs and visionaries? I keep hearing the word relentless. Are you relentless? Are you persistent? How do you term it?

Martin: It’s all of the above, but you really have to immerse yourself in the problem. You can’t just think about something and look for the opportunity. I already told you what the first thing you think of. Should I ask you, or do you have an experience? That’s got to be the first thing any entrepreneur thinks about, because you have to understand the market, and you have to also understand those two words you just used: relentless and persistent. There is no such thing, John, as an easy business. They are all hard. Even podcasting is hard.

John: It’s all hard. I didn’t tell you this, Martin, but my full-time job, this is my part-time job, is that I’m the CEO and co-founder of the largest recycling company of electronics. So we’re very familiar, and very thankful to you for your wonderful invention, because if you didn’t invent this, I probably wouldn’t have a full-time job.

Martin: Well, I accept that accolade because not only do I support you in that regard, but I get a new phone every year, whether I need it or not. Think of all those old phones that you could recycle.

John: So, what have you and your wife worked on together and invented together at Dyna in your 45-year journey together? How have you stayed together working on this as co-entrepreneurs and co-visionaries?

Martin: Well, our most successful things have been the things that we’ve done separately, because Arlene did the Jitterbug. I worked with her and supported her, but the ideas were hers. When you talk about the relentlessness, we both had other businesses started that have not been quite as successful. I did start a company that looked at the future of cellular in the sense that there were not enough radio spectrum, or at least people said that, to support the growth that has occurred, and it will continue to occur. All the technology that I helped create in this company, a company called ArrayComm, is coming to fruition right now. My latest endeavor is I have a hearing problem, and it started when I was in the Navy, the time when I thought I was indestructible, and I would do target practice from the back of a ship with a .45 calibre pistol, and every time I’d pull the trigger, my ears would hurt. What was happening is all these little fibres in my ears that make you hear were breaking off one at a time, so I have bad hearing now. I discover that 10% of the population of the United States, and more in the rest of the world, have serious hearing problems. What you don’t realize is lack of hearing interferes with your ability to communicate with other people, and that is life-threatening. People die from loneliness, so I did discover that there are some voices that are better than others, and so I assembled a team of people, and we are creating a product that is a different kind of hearing aid. It’s not a hearing aid that just makes things louder, because all that does is take those little hairs[?] I was describing and break them off for other reasons. But I have conceived of making any voice that you do not find comfortable. Your voice is very comprehensible, John, but if you have a really bad hearing problem, you might have a little trouble with yours. But clearly, what you’ve been doing for so many years has made you a clearer speaker.

John: So what’s your new device? What did you create that’s going to hopefully revolutionize the hearing aid business?

Martin: I can now, even with our experimental stuff, listen to anybody, people with the highest voices, people with the most non-comprehensible voice, and turn that voice into one that is optimized for my hearing. It actually matches like a jigsaw puzzle. It fits right into the limited capacity to hear [inaudible]. So the reason that somebody like me can do that is that technology is moving so fast, artificial intelligence.

John: So, tell me the differential between your new product and what existed before, and then when will your new invention hopefully be available to the public, because this is a growing problem. I have many people in my family with hearing issues. This sounds like a breakthrough invention.

Martin: Well, I hope that it is. There are a lot of people working on this problem, and the only thing that I contributed to the problem, John, is that I experienced it. I know exactly what the problem is. When our team does demonstrations, they use me as a subject, and that gives us a big advantage over other people. But just to repeat, what we are doing is examining a person and finding out what voices that person can hear well, what the characteristics are of that voice, and changing the voice of other people to fit that pattern. So when I talk to you, I can hear you very clearly because you are an experienced speaker, but if you were a woman with a very high-pitched voice, what I would hear is not your voice, but I would hear the voice of a woman, still a woman’s voice, but with a tone that fits into my hearing pattern, and I would hear that voice perfectly. Furthermore, the thing that is really a killer for those of us that have hearing problems is I could be talking to you. If somebody is holding a conversation in the same room, they would wipe us out. So we have a technique using artificial intelligence where the machine recognizes your voice and optimizes receiving your voice and rejects other voices. So between those two things, what we do is extend the working life and the living life of a huge percentage of the population. People are living longer now, and for their health reasons, the cell phone, as I mentioned before, is helping that process along, but now they’re allowing people to engage and be productive for much longer periods of their life.

John: So, talk a little bit about when do you think this becomes available to the normal population, becomes commercial?

Martin: Well, you are listening at the beginning. In fact, if I was a commercial company, I wouldn’t be telling you all this. I could just see the line[?] cracking in a bunch of your listeners, that, “Mm, that might be a good business for me to try out.” I will have created a whole bunch of competitors, but you understand, I’m not trying to increase my wealth any more than that. I’m trying to increase my lifetime, so if somebody else does it better, that’s fine. It turns out we are at this stage now where we really understand what the problems are, and as usual, there are problems that we never anticipated before. And we’re working hard on solving those problems. We would like very much for when I turn your voice into a new voice that still has some of the qualities that make John what John is. So there are a lot of nuances. I would not expect a commercial product for any sooner than a year or two, but it may be a little costly that you may have to carry. We’re hoping that you could put all this technology into, would you believe, a cell phone. But the first iteration of the thing that we’re working on, you have to use a powerful computer to do that. We know that at some point, every year, the new cell phone comes out. Of course, I always buy it whether I need it or not. The computer in the cell phone is more and more powerful. We know that when we’ve got the rest of the technology worked out, it will go into the cell phone. Ultimately, it’s going to go right into your hearing aid, all that technology.

John: That’s fascinating. Do you still get the same feeling of being a visionary and an innovator and an entrepreneur that you did back in the 60s, 70s, and 80s? Every time you come up with a new idea or a new vision, does it give you life to work on that every day? Is it a challenge and keeps you fresh and young thinking?

Martin: I can’t express it any better than you did. I have to tell you an example that shut me up about talking too much. I just went to a conference the other day. I got a lifetime award for the R-Coding Society. Somebody showed me a book they just published that says that the amount of data that is transmitted in all respects wirelessly is going to start reducing. To me, it’s dumb as saying that you shouldn’t use cell phones in school. I decided that I was going to educate myself. I went to CHAP-GPT, and I started asking questions. I ended up with, essentially, a book that explains why the amount of data in the future is going to keep increasing and increasing. I described to you the health care. I didn’t mention to you transportation. Within a few years, every car is going to be talking to every other car on the street. It’s going to be wireless. If you don’t think that’s going to increase the amount of data, boy, you don’t have any imagination. The ability to reach out and have your mind interact with, as I said before, all the information in the world is so exciting. Everybody can do this. It doesn’t take any special genius. It is mind-boggling to me.

John: Martin, you’re not only a living legend in the electronics industry and the cell phone wireless industry, but you’re now 96 years old. Warren Buffett’s 95. People are living longer, as you said, and they’re living better. Do you have some pearls of wisdom, of advice, you could share with our listeners to not only live long but live well? Your brain is perfectly clear. You look wonderful, very healthy and vibrant. Talk a little bit about how you do this, 96. That’s a heck of a run.

Martin: One thing is, I’m very lucky, but there’s nothing magic about it. It takes a whole bunch of things. The evident one that you can’t control is genetics. Fortunately, I come from a long-living family, but that’s only one factor. The other ones are crucial. Number one has to be attitude. If you don’t have a positive attitude, if you don’t look at life the other way, you don’t get energized, [inaudible] you will not have the motivation to keep going. The second thing is taking care of your body. If I had any brains, I would not have been shooting my pistol off [inaudible].

John: You were young. You didn’t know. What did you know? You were a young kid.

Martin: When they do the target practice now in the Navy, they tell you to wear headphones. In ancient times, when I was in the Navy, they didn’t teach that. Nutrition is really important. Only recently, a friend of mine named Eric Topol has been working on really esoteric living over a long time. One of the things he discovered, and this may affect you, probably not, is that overdoing drinking alcohol is life-threatening. He doesn’t even like the idea of having a single drink or a drink a week. Certainly, using alcohol to improve your attitude is life-shortening. It’s all obvious things. You want to have a positive attitude about life. You want to eat well, exercise well, take care of this body; you only got one of them. Use all of the modern tools to be aware of the diseases that are somehow surrounded by other people’s diseases. You are going to get them. If you do all the other stuff, you are able to resist them. If you have a modern cell phone, it’s going to tell you you’re getting sick. Do so-and-so, and you will not get sick. Do it all, because living longer now is something to look forward to, not just the path toward giving up. I don’t know if that’s inspiring in any way [crosstalk] but I believe in everything I just said. I recommend it for everybody.

John: That’s wonderful. You’ve been with your wife somewhere around 45 years. Any pearls of wisdom for us husbands out there, or significant others, on how to have a long and happy marriage?

Martin: Well, I could use a little help myself. As I said before, when you’re with a woman who’s more intelligent than you are, the most important one is you cannot win an argument. I’m really sincere about that. It sounds like an obvious thing, but anybody that thinks that in a relationship it’s 50-50 is making a big mistake. The only way relationships are maintained is if they’re 80-20. If the other person is 80% of the quality of the conversation, you’ve got a chance of surviving. I haven’t totally convinced Arlene yet. She wins most of the arguments, but that’s worthwhile. She’s wonderful.

John: As I mentioned earlier, Warren Buffett is now almost your age. He’s 95, and he just wrote his final investor letter to his investors. He’s semi-retiring at Berkshire Hathaway. He’s going to become the chairman, but he’s not going to write his letters anymore. In his letter, he said kindness is both costless and priceless. What’s the kindest thing anyone ever did for you, Martin?

Martin: People are just so nice to me my whole life. I would not narrow it down to anything.

John: That’s great.

Martin: The most important thing in my attitude about that specifically is I learn from everybody. I find good qualities in everybody. I start out, when I meet somebody, thinking about what can I do to get an interchange with this person so we make both of us better. I hope that doesn’t sound like I’m lecturing, but it is true.

John: That’s beautiful.

Martin: If you start out being suspicious of people, you build a barrier between you and other people, and that’s the problem with the whole world today. This whole concept of warfare, of people hurting each other, unproductive, unnecessary, stupid. Let’s beat down stupidity. Up with self-love, down with stupidity.

John: So safe to say you’re a people person. You really love meeting people, and you love being engaged with people. You enjoy the personal fluency you’ve built over your 96 years.

Martin: You bet. I value those things very highly, and I don’t reject anybody unless they reject me.

John: Including myself, all parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents, are looking to always be better. Any great advice about being a dad, a grandpa, and a great-grandpa on parenting?

So many times I meet young parents, and they’re so worried that they’re not doing the right thing or they’re going to make mistakes. Any thoughts and pearls of wisdom on your lifetime of parenting and being a father, a grandpa, and a great-grandpa?

Martin: Well, I keep reminding you that I’m still learning, but there is only one important one, and that’s set a good example.

John: That’s great.

Martin: Lecturing to your children or grandchildren never works, but if you set a good example, I have not only my family, but every once in a while, I run into a youngster who is open-minded and likes to exchange ideas. That’s my kind of people, and those are the people that I influence, and they influence me as well.

John: Martin, I’m just going to say this has been the most delightful 90 minutes of this year for me. Personally, it’s an honor to meet you. You and your wife Arlene are in the Consumer Technology Hall of Fame and the Wireless Hall of Fame, and you’re also considered two of the top 10 wireless inventors of all time. I not only thank you for your time today, but more importantly, I thank you for all that you’ve done to inspire entrepreneurs like me, and how you change the world with the cell phone, and you’ve made the world a better place. Martin, thank you from the bottom of my heart. This has been a dream come true to meet you like this and to have this conversation, and thank you for all you’ve done to make the world a better place.

Martin: You’re much too kind, John, but thank you. I really enjoyed it. [inaudible] I wish you the best of luck.

John: This edition of the Impact Podcast is brought to you by Engage. Engage is a digital booking platform revolutionizing the talent booking industry. With thousands of athletes, celebrities, entrepreneurs, and business leaders, Engage is the go-to spot for booking talent for speeches, custom experiences, live streams, and much more. For more information on Engage or to book talent today, visit letsengage.com. This edition of the Impact Podcast is brought to you by ERI. ERI has a mission to protect people, the planet, and your privacy, and is the largest fully integrated IT and electronics asset disposition provider and cybersecurity-focused hardware destruction company in the United States, and maybe even the world. For more information on how ERI can help your business properly dispose of outdated electronic hardware devices, please visit eridirect.com.